Henry VIII is perhaps the best-known English king in history – but his reputation makes him famous for all the wrong reasons. The infamous monarch was known for his sweeping religious reforms, six wives and the many enemies he made, the majority of whom met a cruel end at the hands of an executioner.

In some cases, his own personal feelings urged him toward a particularly brutal or ignoble death for his enemies. Below are eight Tudor executions that show Henry VIII at his most unpleasant and vengeful.

Richard Roose – April 1532

Richard Roose was the cook for John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester. When Fisher held a dinner party, Roose served porridge, which was eaten by the guests and also offered to two beggars who came to the door. The guests became seriously ill, while the beggars died. Fisher was unaffected, since he hadn’t eaten the porridge or anything else that day, leading to suspicions that he’d poisoned the porridge.

Having been arrested on suspicion of poisoning, Roose was tortured until he confessed to having added a white powder to the porridge. It had been given to him by a stranger, and the cook had naively assumed it was a laxative, something that would incapacitate people for a prank, not kill them.

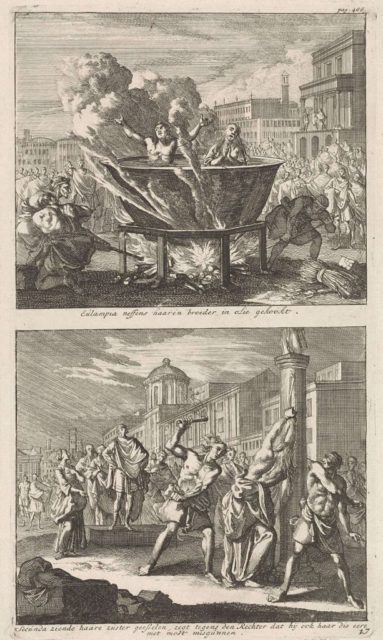

King Henry VIII had a mortal fear of poisoners, so put forward an act of parliament that made poison a treasonous offense, the punishment for which was death by boiling. Since the act had a retrospective effect, it meant Roose faced the unpleasant fate. He was given no trial, nor an opportunity to defend himself; Henry sentenced him to death after “a lengthy speech expounding his love of justice and his zeal to protect his subjects and to maintain good order in the realm.”

On the day of his execution, Roose was tied up in chains and repeatedly lowered into and lifted out of a vat of boiling liquid until he was dead. One onlooker recounted the awful scene, saying, “He roared mighty loud, and divers women who were big with child did feel sick at the sight of what they saw, and were carried away half dead; and other men and women did not seem frightened by the boiling alive, but would prefer to see the headsman at his work.”

Historian G. W. Bernard speculated that Henry’s extraordinary reaction to the attempted poisoning might indicate a guilty conscience and hint at the fact he either had a hand in the attempt or at least knew about it.

Pilgrimage of Grace – October 1537

In October 1536, parts of northern England rose up in revolt against King Henry VIII and the religious upheavals he was implementing. Under the leadership of Robert Aske, the rebellion had some success.

With 30,000-40,000 men under Aske, Thomas Howard (the Duke of Norfolk) and George Talbot (the Earl of Shrewsbury) were forced to negotiate near Doncaster. With a promise of pardons all around and a parliament to be assembled in York, Aske sent his rebels home, pleased that Henry had seen their side of the argument.

However, he never intended to keep his promise. When a new uprising took place, Howard quickly suppressed it, and the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace were arrested. In all, 216 rebels were executed, including lords, knights and abbots. Some were hanged, others beheaded. The unfortunate Thomas Moigne, the MP for Lincoln, suffered the worst death: hanged, drawn and quartered. Robert Aske was hanged in chains, his body placed in a gibbet as a warning to others.

Thomas Cromwell – July 1540

Thomas Cromwell rose to favor when he helped King Henry VIII secure a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. He had a turbulent relationship with Anne Boleyn, but he survived her downfall, with some commentators suggesting he might have had a part in engineering it.

However, Cromwell’s own downfall was imminent after he arranged a marriage for Henry with Anne of Cleves, whom the King didn’t like at all. Henry had seen a flattering portrait of Anne, but her actual appearance repulsed him and he declared he couldn’t consummate the union.

It was powerful enemies like the Duke of Norfolk and Stephen Gardiner, the Bishop of Winchester, who plotted Cromwell’s downfall. Thomas Howard was particularly keen that his niece, Catherine, become queen in Anne’s place. Henry was taken with Catherine, and ensured Cromwell was arrested at a council meeting on June 10, 1540.

Imprisoned in the Tower of London, Cromwell was stripped of his wealth and titles, and it was decreed the man who’d become chancellor should now only be known as “Thomas Cromwell, cloth carder.” While the list of his offenses was long, everyone knew his death was Henry’s revenge for the unwanted marriage.

In some versions, Cromwell’s enemies ensured his executioner was either drunk or sufficiently inexperienced, so he botched the job, taking several blows to sever Cromwell’s head from his body. If true, this would have been a final indignity for a once-proud man.

Margaret Pole – May 1541

When she was imprisoned in the Tower of London, Margaret Pole was 67 years old and considered an old woman by Tudor standards. When her son, Reginald, was marked as a traitor, Margaret wrote to him, reproving him for his folly. However, he continued his criticisms of King Henry VIII’s policies, and since he was out of Henry’s reach in Padua, it was his family who paid the price.

A search of Margaret’s home produced evidence suggesting she still supported the Catholic faith, something Henry had ruled unlawful. She was sentenced to death at the King’s pleasure, and she wound up sitting in the Tower for two and a half years with the threat of execution hanging over her.

When she was told she would die, Margaret refused to believe it or come quietly. She said beheading was for traitors and she was no traitor. When she refused to put her head on the block, her jailers forced her down onto it. Even then, she twisted her neck this way and that way in protest.

To make it even worse, Margaret’s executioner was inexperienced and reports suggest it took 11 blows before she was dead. The Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, witnessed the execution and wrote that it was “a wretched and blundering youth who literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner.”

Thomas Culpeper and Francis Dereham – December 1541

While King Henry VIII might have initially been pleased to be married to a young and flirtatious Catherine Howard, his happiness was not to last when she had an affair with Thomas Culpeper, one of Henry’s favorite courtiers. Francis Dereham also became caught up in the controversy, although with a charge of sleeping with Catherine before she was married to the King.

Both men were sentenced to death and petitioned Henry to have their traitor’s death commuted to beheading. Even though Culpeper’s crimes were arguably greater than Dereham’s (since he’d slept with Catherine while she was queen), his request was granted, while Dereham’s was not.

On December 10, 1541, both men were executed. A report at the time described the scene, reading “Culpeper and Dereham were drawn from the Tower of London to Tyburn, and there Culpeper, after an exhortation made to the people to pray for him, he standing on the ground by the gallows, kneeled down and had his head stricken off; and then Dereham was hanged, membered, bowelled, headed, and quartered [and both] their heads set on London Bridge.”

Jane Boleyn – February 1542

Another courtier to be swept up in Catherine Howard’s disgrace was Jane Boleyn, Viscountess Rochford. Jane survived the scandal that had seen her husband, George, beheaded for a relationship with his sister, Anne. She returned to court, where she served Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves and Catherine Howard when they served as queen.

When Catherine was accused of adultery, Jane was implicated as an accessory and was taken to the Tower of London, where she was interrogated (although not tortured). This led to her having a nervous breakdown and being declared insane at the beginning of 1542.

The law at the time meant those declared insane could not stand trial. However, with her name linked to both Catherine Howard and Anne Boleyn’s disgraces, King Henry VIII was determined that Jane be punished. As such, he overturned the law and made an exception that, when a person was accused of high treason, they could be tried and executed.

Both Jane and Catherine were executed on February 13, 1542. Their bodies were buried at the Tower of London, close to where Anne and George had been laid, a stark reminder that no one could outrun Henry’s vengeance forever.

Anne Askew – July 1546

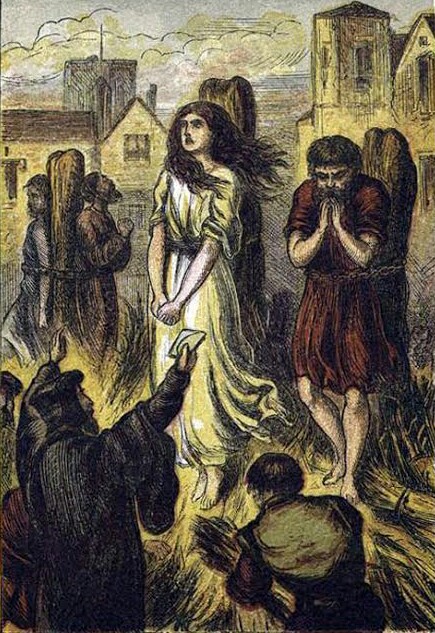

A relative of Robert Askew, Anne was one of only two women to have been tortured at the Tower of London and burnt at the stake. She drew attention to herself by preaching as a Protestant. An attempt to transport her to Lincolnshire and keep her there failed, as she escaped and returned to London to continue her sermons.

After several brushes with the law, Anne was arrested for a third time in May 1546 and taken to the Tower of London. She was placed on the rack, in the hope she would give up other Protestant names to her torturers, but she didn’t. When she was taken to her place of execution in Smithfield, she had to be carried in a chair because she was so crippled by her torture.

Beside her at the stake were three other Protestants. An unknown sympathizer had slipped bags of gunpowder to all of them, which ignited in the flames. The four were blown up and thus saved from the agonizing death of being burned alive.

Anne Boleyn – May 1536

Virtually everyone knows the life and fate of Anne Boleyn, and while she had a swifter and more merciful death than those listed above, she makes this list because King Henry VIII’s mercy might actually have been his usual cruelty in disguise. When Anne knew she was going to die, she asked for a French swordsman to be summoned to execute her. Being beheaded by a sword was swifter and cleaner than beheading by an axe. As a sign of mercy, Henry agreed.

However, the man chosen to behead her was an expert swordsman from Saint-Omer, France. It was necessary to order him from France and allow time for him to cross the English Channel. The Anne Boleyn Files and other sources point out that, if the swordsman was to be there for the planned execution date of May 18, 1536, then he needed to be ordered on the 12th or 13th of May, perhaps even as early as the 9th or 10th.

More from us: Clementine and Winston Churchill’s Enduring Relationship

However, Anne’s trial only happened on May 15, 1536, meaning Henry must have ordered the headsman even before the trial took place, suggesting Anne’s fate was already sealed before she’d a chance to defend herself.