The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum was originally built to house 250 souls, but today the abandoned facility is home to countless spirits that still haunt the hallways.

The grim history of mental health care

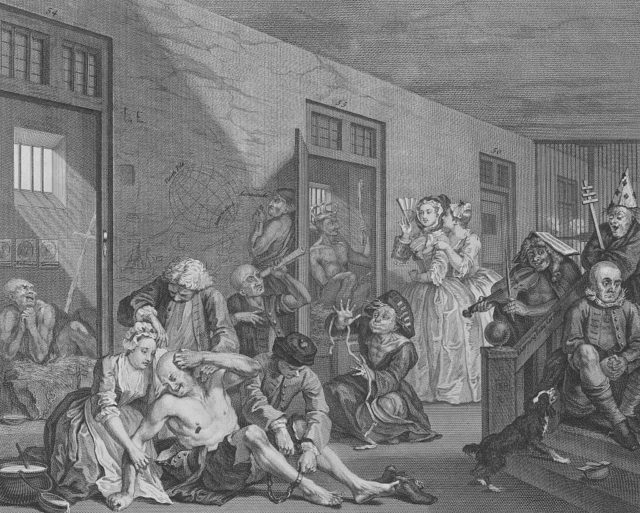

When colonists first arrived in the New World, they brought with them a complicated perception of mental illness that would ultimately lead to the creation of asylums like Trans-Allegheny. People exhibiting strange behaviors were often suspected of being possessed by demons or in league with the Devil, triggering events of mass hysteria such as what occurred during the Salem Witch Trials in 1692.

By the early 18th century, the treatment of mentally ill people continued to decline. Anyone without family, friends, or finances to help take care of them was placed in prisons where they were chained to the walls with no proper sanitation or care. Many were given the same treatment within the confines of their own homes, kept locked in attics, basements, and sheds.

In the 1770s, special facilities were constructed to house and care for the mentally ill but these were not much better than the prison approach. Instead of a treatment-focused center that could help to rehabilitate struggling individuals, these asylums were essentially holding tanks to keep undesirables out of the public eye. Many patients were treated as if their condition was incurable.

The Trans-Allegheny Asylum was built between 1858 and 1881, around the same time that activists like Dorothea Dix began to speak out against the horrific conditions of mental hospitals. Laws eventually came into effect that provided these institutions with proper funding to provide more humane care.

The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum was meant to fix the broken system

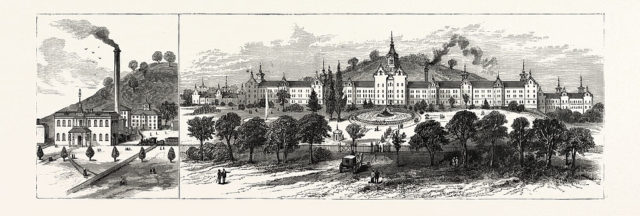

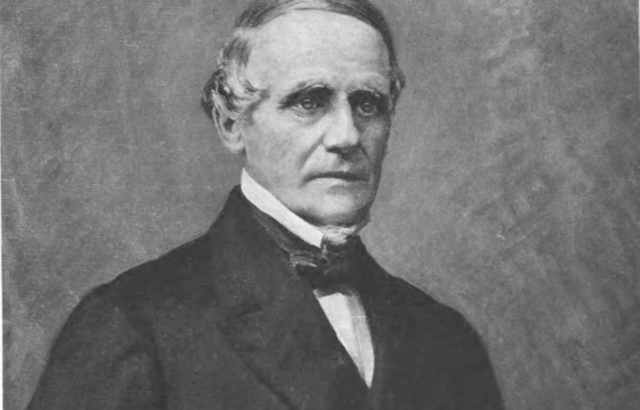

The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in Weston, West Virginia was first authorized by the Virginia General Assembly in the early 1850s following consultations with the superintendent of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Thomas Story Kirkbride. Kirkbride provided the Virginia General Assembly with a plan called the “Kirkbride plan,” a system of mental asylum design.

The plan was a cutting-edge design that focused on transitioning patients from overcrowded jails to “tastefully ornamented” landscapes and a large building with meandering wings and hallways with plenty of windows and fresh air. Kirkbride’s plan helped to inspire the construction of 300 other facilities across Canada and the United States. The facilities were designed to be self-sufficient by designating specific chores and tasks for patients. Kirkbride called this concept “building as cure,” but the theory was debunked by the 20th century.

The Trans-Allegheny building was designed by architect Richard Snowden Andrews in the Gothic Revival style and was built mostly by local prison laborers. The construction of the building was delayed when the Civil War broke out in 1861.

During the war, the Virginia government demanded that the unused asylum construction funds be returned to be used in the war effort. Before the money could be pulled away from the asylum, the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry stole the money from a local bank and handed it over to the newly formed Reorganized Government of Virginia. The Reorganized Government then put the money back into the asylum project and construction resumed in 1862.

By 1864, the first patients were admitted to the asylum – now named the West Virginia Hospital for the Insane – even though construction continued until 1881. The hospital included amenities to ensure it would be self-sufficient, including a farm with dairy cows, waterworks, and a cemetery. The hospital was originally designed to house 250 patients, but by 1880 the population had exploded to 717 patients. At its peak, Trans-Allegheny housed 2,600 people in the 1950s.

Horror and neglect led to the end of the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

By this time, Kirkbride’s vision of a compassionate care facility was long forgotten as patients suffered from the effects of overcrowding and poor sanitation. The awful conditions of the asylum led to an overwhelming number of deaths. While no official number was ever recorded, historians believe as many as 500 patients died on the premises.

Trans-Allegheny’s darkest chapter in its history also happened around the 1950s when it became the home of the West Virginia Lobotomy Project. Led by Dr. Walter Freeman, the project aimed to reduce the number of patients in asylums by “treatment” with lobotomies. Patients were also subject to ice water baths, electroshock therapy, and seclusion cells.

By the 1980s overcrowding was lessened, thanks to improved treatments for mental illness like medications and talk therapy, though some patients deemed “untreatable” were left locked in cages. The asylum was officially closed in 1994, but Trans-Allegheny’s story doesn’t end there.

Ghostly encounters

Many believe that the asylum is haunted by the countless souls who met a horrific end inside the hospital’s walls. Visitors have reported apparitions and heard voices and unexplainable sounds. The most well-known ghost at Trans-Allegheny is Lily, a nine-year-old girl who died from pneumonia. Her room is still filled with her toys, which are said to move on their own.

More from us: Marilyn Monroe was Allegedly Committed to a Mental Asylum Against her Will

Today, visitors can pay for their own private eight-hour ghost hunt inside the asylum where guides help ghost hunters to experience paranormal activity. In the former asylum cemetery, the graves of over 2,000 former patients are all that remain of the waking nightmare they endured during their stay – leading many to believe that some of their souls will be trapped in the confines of the asylum forever.