Deep in the mountains of West Virginia lies the once-booming ghost town of Thurmond. Advancements in technology and the Great Depression are just two of the factors that lent themselves to its rapid decline. Today, the town is home to five residents and a railway station serviced by Amtrak only three times a week.

A coal miner’s dream town comes into existence

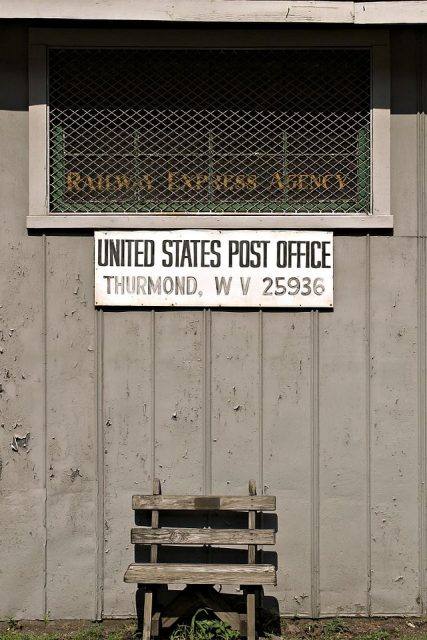

Thurmond’s history dates back to 1873, when Confederate Army veteran Captain W.D. Thurmond was given 73 acres along the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway mainline. The establishment of a post office in 1888 allowed for the establishment of a small settlement, and the population steadily grew with the construction of a crossing over Dunlop Creek in 1892 and addition of a railroad station.

Thurmond was incorporated in 1900 and quickly became the heart of the New River Gorge, as its railway allowed for the efficient movement of coal. Along with the local timber industry, this allowed the town to continue its growth.

A thriving boomtown

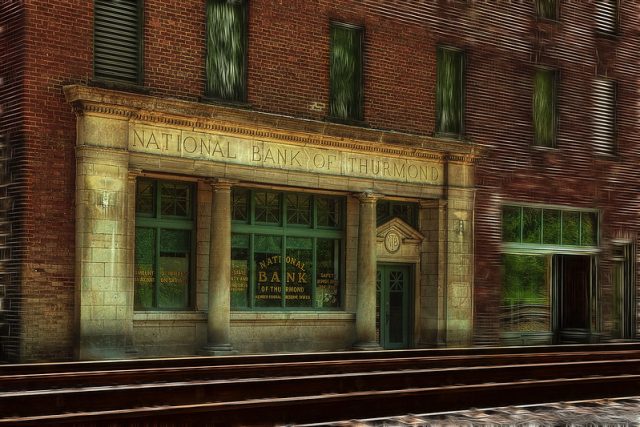

During the first two decades of the 1900s, Thurmond was a boomtown. By 1910, it was the center of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, producing $4.8 million in freight revenue. This exorbitant amount meant the town’s banks were among the richest in West Virginia.

Until 1921, the only way to access Thurmond was via railroad. As such, fifteen passenger trains came through each day, and its depot served 95,000 customers per year. Coal rolled out daily, transporting the power of New River Smokeless Coal from the West Virginian mountains to other areas.

Its rail yard was lined with a passenger depot, a turntable, an engine house, coal and sand towers, and a water tank. Its residential buildings were standardized, with three or four styles corresponding with different positions in the railroad hierarchy.

At its peak, Thurmond was home to 500 residents and had many small businesses. These included two hotels, restaurants, two banks, clothing stores, a jewelry store, several dry-goods stores, business offices, a meat-packing plant, and a movie theater.

In line with the era’s prohibition attitudes, Thurmond banned alcohol consumption. One of its hotels, the Dun Glen, sat just outside the town’s limits and quickly became its red-light district. It was also the site of the world’s longest poker game, which lasted 14 years.

The Great Depression and Thurmond’s quick decline

There are many reasons for Thurmond’s decline. It was kickstarted by the Great Depression, which resulted in the closing of the National Bank of Thurmond in 1931. This was followed by the moving of the New River Bank to Oak Hill in 1935. The meat-packing plant and the telephone district office were closed in 1932 and 1938, respectively.

Just a year before the closing of the National Bank, the Dun Glen burned down, marking the first of two major fires to devastate the town. The meat-packing plant went up in flames in 1963.

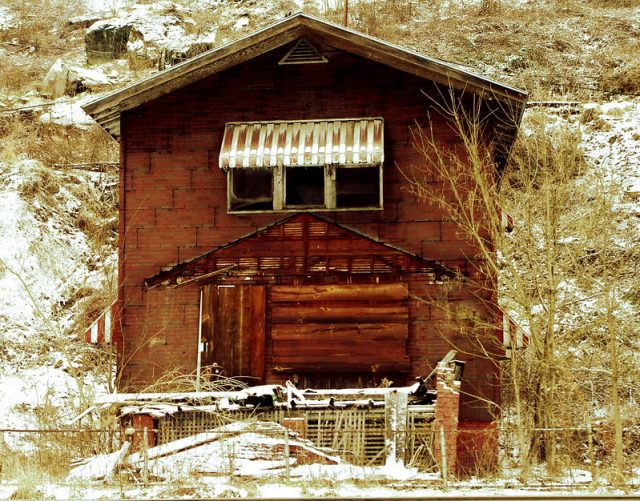

Along with its failing economy, Thurmond fell victim to the advent of the diesel locomotive and the increasing popularity of automobiles. During the mid-1930s, the public began traveling more by car, largely due to the construction of better roads, and the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway switched to diesel locomotives in the 1940s. As Thurmond and its rail facilities were geared toward steam locomotives, the town’s structures and jobs became obsolete.

The town’s businesses shut down and its residents moved to other communities.

A designated historic district

While Thurmond was a virtual ghost town by the 1950s, efforts have been made to draw tourists to the area. In the 1960s, the town became home to Wildwater Unlimited, a commercial rafting company operating along the New River. Construction of the New River Gorge bridge in 1977 also allowed visitors better access the once-isolated town.

The town has since fallen under the control of the National Park Service, which designated it a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1995, it restored the railroad station and turned it into a visitor’s center. At present, over 20 structures remain, including the National Bank, the Lafayette Hotel, and other commercial buildings.

In 2003, the service began a stabilization program to repair and preserve the remaining buildings. This work includes the improvement of drainage around the buildings; the removal of overgrown vegetation; the installation of metal panel roofs and gutters; exterior restoration work; the removal of hazardous porches and additions; and the installation of window louvers to provide more adequate interior ventilation.

Thurmond’s sidewalk has been restored by the Boy Scouts of America. Its members set it with commemorative brickwork, which details the town’s rise and fall. The last brick is engraved with a “thank you” to the organization for its work.

More from us: 5 North American Ghost Towns That Satisfied Our Inner Adventurer

According to the 2010 census, Thurmond is home to five residents: three council members, a mayor, and a town recorder. No businesses are open along the main street, but the rail station is still in use. Amtrak currently makes three stops a week in Thurmond on a “request a stop” basis.