History is typically thought of as a one-sided, objective retelling of events. But just like any story, the past is never black and white. The treatment of America’s Indigenous peoples is one chapter of history that is often misrepresented or even left out entirely – and the truth about Native American boarding schools is one part of a dark past that is finally coming to light.

In May 2022, the US Department of the Interior released a comprehensive report on the history and ongoing generational legacy of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. The investigation set out to examine the “loss of human life and lasting consequences” of the boarding school system.

Schools were one step in a plan to assimilate Native Americans

Indigenous peoples and nations have resided in North America since time immemorial. It wasn’t until European explorers like Christopher Columbus arrived looking to create a “new world” that the idea of influencing, controlling, and even exterminating Native Americans began to take shape.

America was built as a settler colonial nation, a system that requires the conquest of land and resources – both of which belonged to Indigenous peoples. A series of wars, treaties, and policies were established between settlers and Indigenous that allowed the American colonies to take shape. Unfortunately, many of the treaties and agreements were disrespected or left unfulfilled.

Fast forward to the early 19th century and Indigenous people are still not only alive but continue to carry on their cultures, languages, and traditions. In 1819, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act which authorized annuity payments that encouraged the assimilation and “civilization” of Native Americans.

The civilization effort was furthered by the Peace Policy of 1869, which was advanced by President Ulysses S. Grant to remove the corrupt Indian agents and replace them with Christian missionaries. In doing so, thousands of missionaries traveled throughout the country in an attempt to convert Indigenous people who they saw as “savages” and “pagans.”

Unfortunately, some of these stereotypes persist today. In dehumanizing Indigenous peoples by calling them “savage” or “uncivilized,” those looking to profit off Indigenous lands and resources could justify the erasure of an entire group of people based solely on their identity. This is considered cultural genocide when one group is targeted this way and forcibly coerced to assimilate into another society.

‘Kill the Indian, save the child’

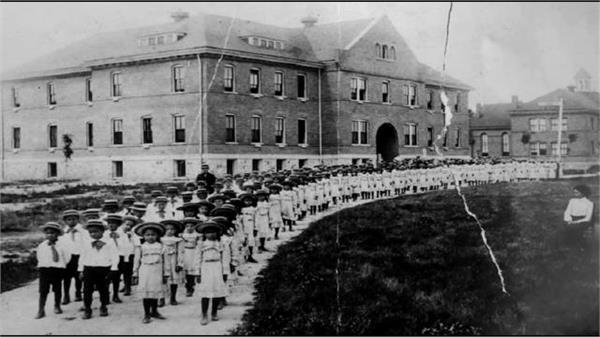

Soon several religious Christian denominations adopted a boarding school policy which was, according to The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, “expressly intended to implement cultural genocide through the removal and reprogramming of American Indian and Alaska Native children to accomplish the systematic destruction of Native cultures and communities.”

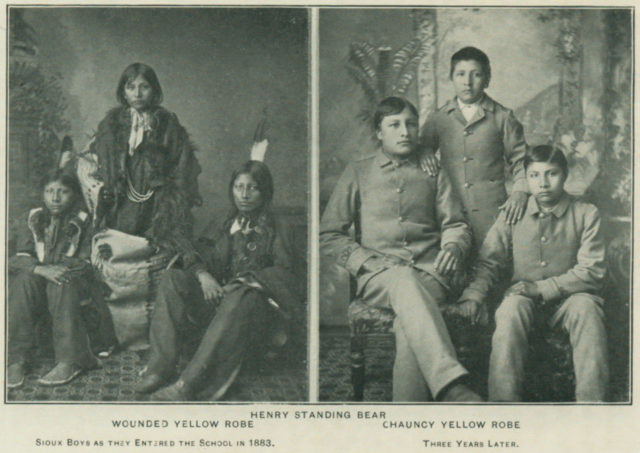

The approach for these schools can be summed up in a phrase first used by Captain Richard Henry Pratt during a speech delivered in 1892 at the National Conference of Charities and Correction in Colorado. In order to “save” Native Americans, they must “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” This exact framework was employed against children in boarding schools across the country for over 100 years.

From 1869 to the 1960s, thousands of Indigenous children were removed from their families and communities, alienated from their cultures and traditions. By 1900, 20,000 children were living in Indian boarding schools, and in just 25 years that number tripled. Between 1819 and 1969, the Indian boarding school system consisted of 408 residential schools across 37 states or territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and seven in Hawaii.

Children as young as four years old were either forcibly or voluntarily taken from their homes to live in the schools full-time. This was believed to ensure a more thorough “assimilation” into society, and the schools were often located far away from students’ families. Their traditional names and belongings were stripped from them, Indigenous languages were banned, and children were punished if overheard speaking them. Long hair and braids were cut off, and siblings were frequently kept separated.

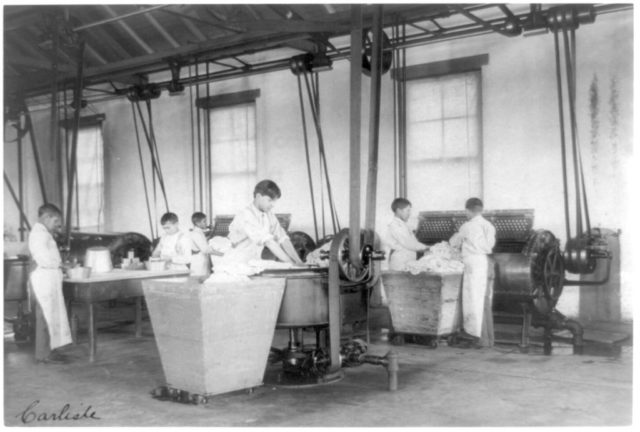

The majority of time spent at “school” had little to do with education. Students were often required to do manual labor which, according to the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, included: “livestock and poultry raising; dairying; western agriculture production; fertilizing; lumbering; brick-making; cooking; garment-making; irrigation system development; and working on the railroad system.”

Unmarked graves reveal the genocidal history of boarding schools

Abuse and neglect ran rampant through the Indian boarding schools. Many children faced physical, sexual, mental, and spiritual abuse at the hands of administrators and church officials who ran the schools. Some of the most devastating atrocities that happened in schools have yet to be discovered. Countless unmarked graves continue to be unearthed each year, with over 50 known burial sites associated with the board school system thus far.

The report released by the Department of the Interior revealed that the investigation has so far turned up 500 deaths across 19 schools, but that number is expected to climb into the thousands. The American government was prompted to look into the history of boarding schools and unmarked graves of Native children after the unmarked graves of 215 children were discovered on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada.

More discoveries have since followed, including a discovery of 750 graves in Saskatchewan. Thanks to the research conducted by the Department of the Interior, we now know that similar circumstances also occurred in the United States. Both the US and Canada have called the mass deaths and abuses at the boarding schools a cultural genocide.

While both Canada and America share a similar history with Indian boarding schools, significantly fewer Americans are aware of the existence of these schools than Canadians.

The number of Canadians who knew about Indian boarding schools or residential schools was 30 percent before the federal government launched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to gather information and survivor’s stories, and educate the general public. Since the TRC was published, 70 percent of Canadians are now aware of the abuses that took place in Canadian Indian schools. In the US, on the other hand, it is estimated that less than 10 percent of Americans know about the history of US Indian boarding schools.

How historical trauma shapes today

Even though Indian boarding schools closed their doors in the 1960s, countless victims, along with their descendants and communities, continue to live with the realities of abuse and cultural genocide. The effects of trauma can be carried on through generations, in what Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart describes as “the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over one’s lifetime and from generation to generation following loss of lives, land and vital aspects of culture.”

A White House Report on Native Youth released in 2014 confirmed how historical trauma is affecting modern-day Indigenous people, especially youths, in disproportionate ways. Major disparities in health and education for Native communities are ongoing, as well as an epidemic of youth suicide and PTSD rates which are three times that of the general public – the same rate as Iraqi war veterans.

More from us: Why Are People Still Partying on Plantations?

As more unmarked graves are found and stories revealed, long-forgotten traumas can reappear. At the same time, survivors of the boarding schools have been speaking out about their experiences for decades but the media and non-Indigenous Americans are only now waking up to the centuries of violence enacted toward Native peoples. Now that survivors are being heard and more initiatives to find unmarked graves and record experiences of the schools, we can also take the vital first steps towards healing.