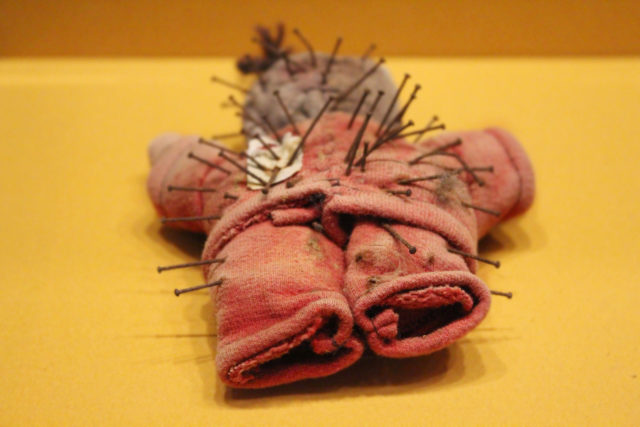

Ritual sacrifice, curses, dolls, and black magic all likely come to mind when you think of Voodoo, but the vastly misunderstood religion has become more like a scary story to outsiders. The real Voodoo origins reveal a different dark side, one where sensationalized racism and propaganda run rampant.

Voodoo was born out of the horrific effects of the slave trade. Today, it attracts tourists fascinated with the unfamiliar and bizarre who are ultimately met with an entirely different reality of the small religion.

Voodoo origins

The history of Voodoo (or Voudou) has nothing to do with witchcraft or demonic worship as it’s often misrepresented in the media. It is actually a folk religion born out of survival. Originating in Haiti, Voodoo was created by enslaved people who were forced to assimilate into a new world with entirely new beliefs. The religion combines traditions from western and central Africa with the new world’s Roman Catholic ideology.

Voodoo began with Christopher Columbus, who arrived in the Americas in 1492 and established his first colony, Hispaniola. The newcomers brought diseases that decimated the local Indigenous population. Soon, the wealthy settlers of Hispaniola turned to slavery to populate their plantations with free labor.

When the first African slaves arrived at Hispaniola, it kicked off a regime of racial violence that would continue in America for another 350 years. Many of the original slaves in America were prisoners of war with backgrounds in traditional African religions, while others practiced faiths that had already incorporated Catholicism.

By the 17th century, the French had established their own Caribbean colony known as Saint-Domingue. The colony exported large amounts of sugar, coffee, and cocoa back home to Europe. As the plantations grew, so did the need for slave labor. By 1790 there were more African slaves than European settlers on Saint-Domingue.

In 1685, King Louis XIV passed a law known as Code Noir which banned the practice of African religions on Saint-Domingue – one of the few things enslaved people could keep with them from their former homes. The law compelled slave owners to ensure their slaves were baptized into the Roman Catholic religion, but many refused to comply fearing that the new religion would encourage congregation and potentially inspire a revolt.

Enslavement directly destroyed the very fabric of African cultures and religions, which were largely focused on family connections and the local community – both of which were stripped away by slavery. Gradually, slaves combined what they remembered from their backgrounds and religions into one larger amalgamation. These religions were practiced in secret and were often concealed using Catholic symbols or references. Eventually, the two religions combined to form the basis of Voodoo, like the connection between African spirits and Catholic saints.

Historians believe that a large percentage of African spirituality connected to Voodoo comes from modern-day Benin, where similar Voodoo rituals still take place.

The Haitian Revolution brings Voodoo to America

Historians regard the Haitian Revolution as one of the largest and most successful slave rebellions in the Americas. The revolution took place in 1791 shortly after the French Revolution. Voodoo is thought to have played a large role in the revolution, especially since two of its early leaders, Dutty Boukman and Francois Mackandal, were believed to be powerful houngans – male Voodoo priests.

In fact, according to local folklore, Voodoo had a direct role in the start of the revolution. The story says that in the summer of 1791, local slaves gathered in the forest at Bois Caïman, a French colony in Saint-Domingue. A Voodoo priestess or mambo named Cécile Fatiman led a ceremony and prophesied that there was a revolution coming.

Fatiman slit the throat of a black creole pig and gave the blood to the three men she believed would usher in the revolution: Jean François Papillon, Georges Biassou, and Jeannot Bullet. The men drank the blood and swore to destroy their French oppressors. The story even claims that storm clouds and thunder gathered as the ceremony progressed.

Soon after, the island of Saint-Domingue defeated the French military and declared its independence under the new name Haiti.

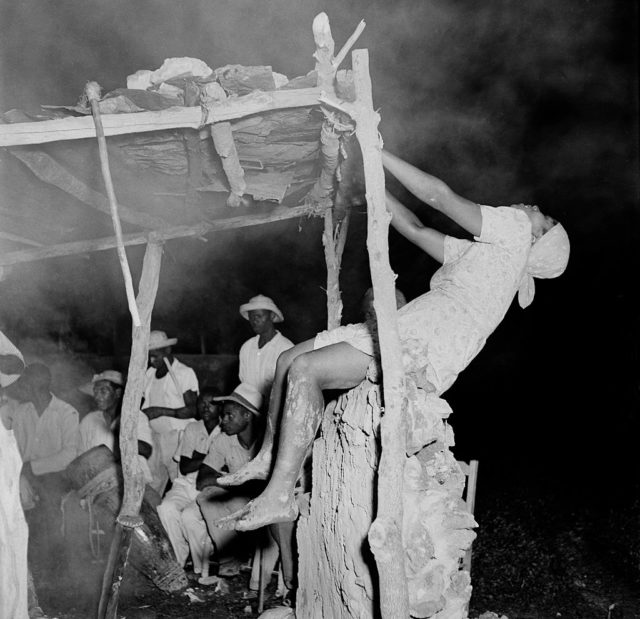

The revolution disrupted the entire fabric of society, allowing slaves to create lakous – compounds where families all lived and farmed together. Voodoo thrived in the lakous, which enabled practitioners to pass on their knowledge of the religion and its ceremonies to their descendants. Combined with the extirpation of the Catholic church from Haiti and the increased connection between practitioners, Voodoo transformed from a select group of “cults” to a standardized religion.

Around the same time, many slaves traveled to what is now Louisiana, bringing Voodoo with them. Today, the city of New Orleans is notorious for Voodoo rituals and attractions that draw in countless tourists each year, who hope to encounter life-changing prophecies of their own.

Lwa: The Spirits of Voodoo

The hybridization of traditional African spirituality with Christian ideology allowed enslaved people to hold on to one of the last remaining semblances of their homes and the last ways to control their daily lives, while also flying under the radar and appearing to adhere to the Code Noir law.

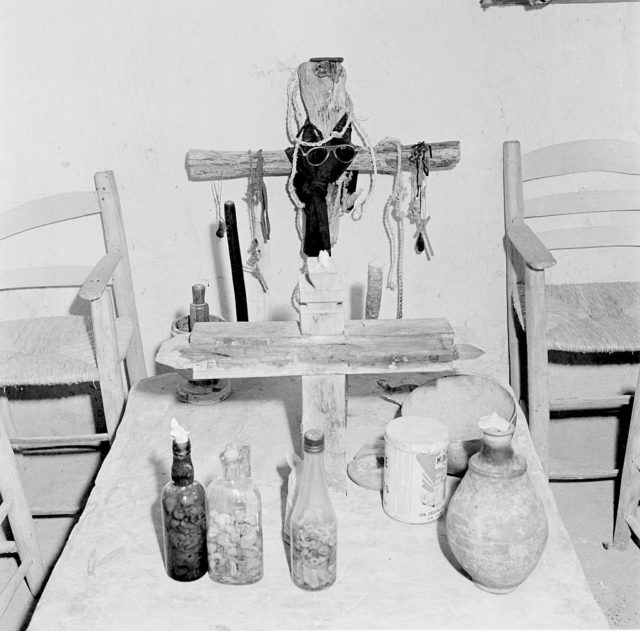

Voodoo practitioners, also known as vodouisants, worship a pantheon of spirits known as lwa that act as intermediaries between humans and the supreme God or creator known as Bondye (meaning the “good God”). Like Christianity, Voodoo is a monotheistic religion. Several important symbols and rituals in Voodoo are also directly related to Christian practices including baptism, the Lord’s Prayer, the use of candles, and the cross. The lwa of Voodoo are closely related to Catholic saints.

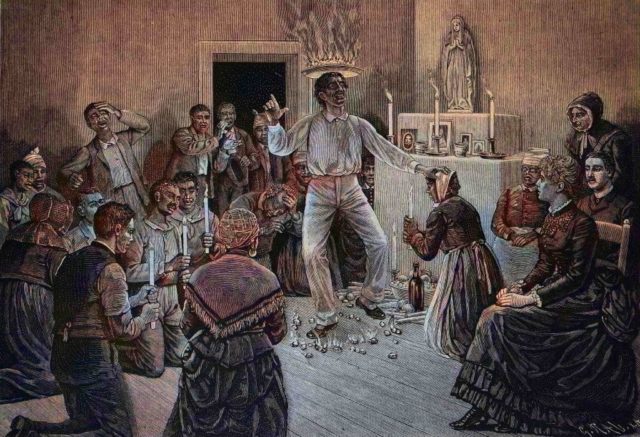

While some aspects of Voodoo are closely related to Catholic beliefs, others are entirely opposite. Possession, for example, is a positive way to communicate with spirits or lwa and promote healing or give guidance. Lwas can also inhabit trees, water, air, and fire and represent various aspects of human life like agriculture, love, war, and death.

Sacrifices play an important role in Voodoo, but unfortunately, this is also one of the most misunderstood Voodoo practices. Animal sacrifices are used to call upon lwas or “feed” them. Some also prefer to be fed with offerings of specific foods. Legba, the guardian of the Lwa, is known to love offerings of meats and vegetables.

Why is Voodoo so misunderstood?

Voodoo is a religion just like any other with its own customs and beliefs, but it is one of the few faiths practiced in the United States that is not fairly represented or understood. Many associate Voodoo with black magic, devil worship, and witchcraft, but as historian Michelle Gordon has explained, these narratives were used to “establish black criminality and hyper-sexuality as ‘fact’ in the popular imagination.”

Voodoo was created as a means to cope with being torn away from one’s home through the slave trade, and continues to be a way that modern descendants of African slaves can stay connected to the beliefs and cultures of their ancestors.

The belief that Voodoo is inherently evil and primitive helps to justify acts of racism throughout American history, including slavery and segregation. The media often chose to depict Voodoo and its practitioners as villains, creating sensationalized stories of human sacrifice, abuse, and even zombification that were meant to frame Haitians and other African Americans as barbaric.

More from us: Who Discovered America? Columbus Is Only Part of the Story

In reality, the true barbarians were the people who participated in the enslavement of thousands of Black men, women, and children, and those who furthered racism through segregation, civil rights abuses, and stereotypes in the post-Antebellum period.