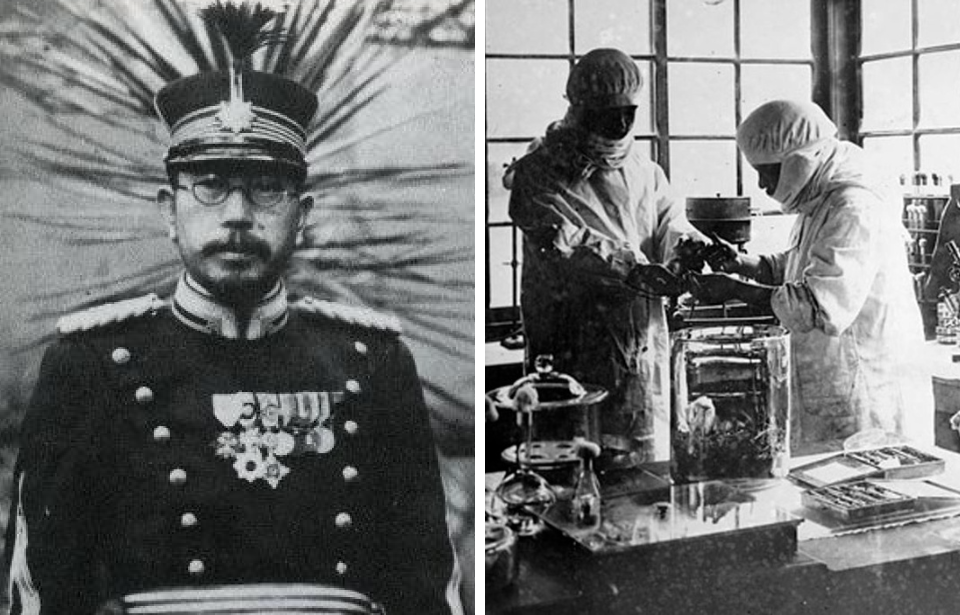

Japanese physician Shiro Ishii oversaw some of the most horrific medical experiments in recent history as the commander of Unit 731 during the Second World War. From testing biological warfare to live dissections of victims, Unit 731 committed crimes against men, women, and children that we can hardly fathom today.

The early life of Shiro Ishii

Shiro Ishii was raised in feudal Japan where his family was the largest landowner in the community. One of four children, his father was a local sake maker. From a young age, he was described by his classmates as “brash, abrasive, and arrogant.” After completing his medical studies at Kyoto Imperial University in 1920, Ishii was commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Army as a military surgeon and impressed his superiors so much that he was invited back to Kyoto Imperial University to conduct post-graduate research in 1924.

According to some who worked with Ishii during this time, he exhibited “pushy behavior” and “indifference” toward his classmates. Instead of human friends, Ishii preferred his bacteria “pets” he grew in Petri dishes that he kept as companions. He would also stay late in the labs, using equipment students had painstakingly cleaned and deliberately leaving the dirty instruments behind in the hopes that other students would be punished. This strange, dissociative behavior would ultimately lead to Ishii’s treatment of human subjects as objects to be tortured without any scientific reason.

By 1927, Ishii was widely advertising his interest in creating a Japanese bio-weapons program to research new biological and chemical warfare applications, two years after Japan signed the Geneva Protocol, banning the use of “Asphyxiating, Poisonous, or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare.” In early 1931, Ishii was promoted to Senior Army Surgeon, Third Class, thanks to the many long nights he worked late in the lab and his extreme loyalty to Emperor Hirohito. He also was known to be a heavy drinker, womanizer, and frequent embezzler.

Unit 731

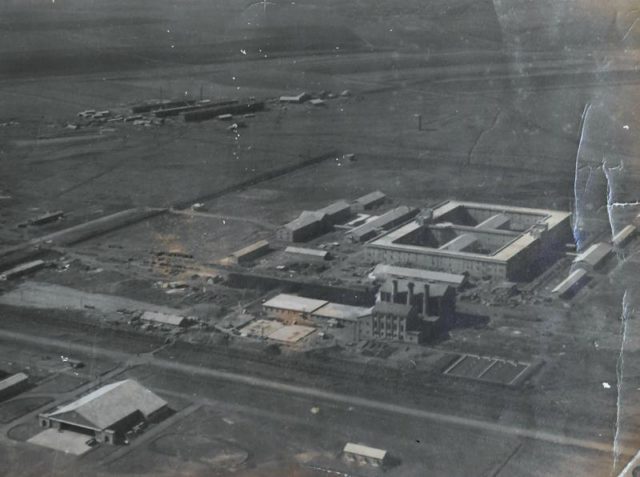

At the time of Ishii’s promotion, China and Japan were embroiled in a tense war. Once Japan gained control of Chinese areas like Manchuria in 1931, they had the perfect opportunity to establish testing facilities with an unlimited supply of Chinese prisoners to use in the horrific experiments.

Ishii’s earliest testing center was the Beiyinhe facility known as Zhongma Fortress in Beiyinhe, China. One thousand prisoners were crammed into the facility and forced to undergo tests like extreme blood drawing every three to five days until they were too weak to go on. The site was closed in 1936, and by that time Ishii was already planning the creation of a facility used to conduct much more sinister experiments.

Ishii was promoted to Senior Army Surgeon, Second Class and in 1936 he was placed in command of the now notorious Unit 731. The unit was a covert chemical warfare research and development organization, disguised as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army – but 731 was neither an epidemic prevention department nor chemical warfare research center. Behind the bureaucratic smoke and mirrors, Unit 731 was implemented to legitimize the deliberate torture and murder of innocent people under the guise of science and progress.

Under Shiro Ishii’s command, 731 took part in a special project dubbed Maruta, where human beings were used as test subjects. Maruta is the Japanese word for “logs,” a nod to what test subjects were jokingly called by their tormenters. The official cover story for the 731 facilities was that it was a lumber mill, so researchers and guards would call prisoners and victims “logs” as a way of keeping the project secret, using it in contexts like “how many logs fell today?”.

The horrors of Shiro Ishii’s plague-bomb obsession

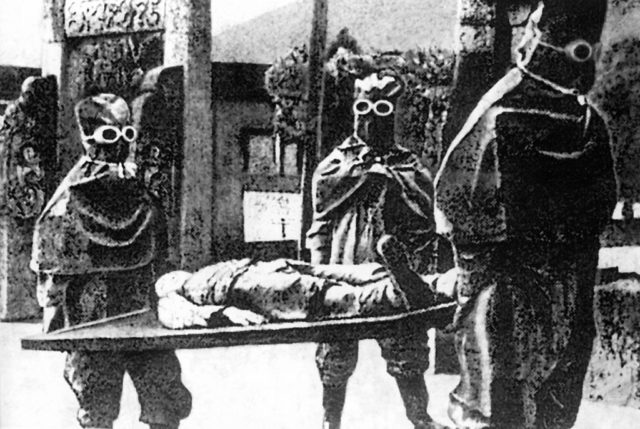

Prisoners were injected with diseases, forced to undergo vivisections without anesthesia, and subjected to all sorts of medical experiments. Limbs were amputated to study blood loss, people were locked in rooms with heat fans to better understand the effects of temperature and dehydration, and women were frequently raped in order to provide babies for use in experiments. Many experiments relied on simulations of real-life scenarios to help medical experts better understand how to treat injuries within the military.

Some prisoners had their hands frostbitten by standing in the cold with hands drenched in water so physicians could learn how to cure it. Others were placed in centrifuges until the high pressure caused their eyes to pop out of their heads to understand how much pressure the body could undergo.

Much of Unit 731’s disease research was part of Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, a plan spearheaded by Ishii to release plague-infected rats throughout Ally-occupied areas during World War II. The plan was never realized, but countless lives were already lost in the alleged “research” phase of the project.

At least 12 large-scale field trials were carried out in 11 Chinese cities. Just one attack in 1941 left 10,000 locals and another 1,700 Japanese troops dead due to cholera. An idea proposed by Ishii, smallpox, anthrax, botulism, and bubonic plague were placed in defoliation bacilli bombs or flea bombs and dropped throughout populated areas. Poisoned food and candy were also handed out to children and villagers.

Once the disease bombs were released, researchers wearing hazmat suits observed the unsuspecting victims. By 1945, the Japanese were prepared to go ahead with Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, planning to release thousands of plague-infested rats along the coast of California on September 22, 1945. The Japanese surrendered to the Americans five weeks before that date arrived.

Ishii was the architect of these experiments who had a hand in each death. He was often compared to German doctor Josef Mengele, who performed similar experiments on Jewish prisoners in concentration camps during WWII.

Shiro Ishii’s war crimes

Shiro Ishii was finally arrested by the United States during the Occupation of Japan following WWII, but he would never be served the justice he deserved. Ishii and his team arranged a deal to receive immunity in exchange for his knowledge of the Japanese military and their experiments. The Japanese medical experts interviewed by US officials insisted they were mere microbiologists. One American who interviewed Ishii’s men stated that the information they provided was “absolutely invaluable.”

More from us: Cold As Rice: How Meals Turned Deadly in 19th Century Japan

After the immunity deal was concluded in 1948, Ishii was never prosecuted for any war crimes. He disappeared from public view for years. Some believe he went to Maryland while others said he remained in Japan and worked as a doctor. He died on October 9, 1959, from throat cancer in Shinjuku, Tokyo.