In 1942, 18-year-old Truman Capote started working as a copyboy at one of the most prestigious modern publications, The New Yorker. Capote would go on to write some of the most iconic works of the 20th century, including In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. However, what began as a start of a promising career at The New Yorker was ultimately cut short thanks to another famed writer: Robert Frost.

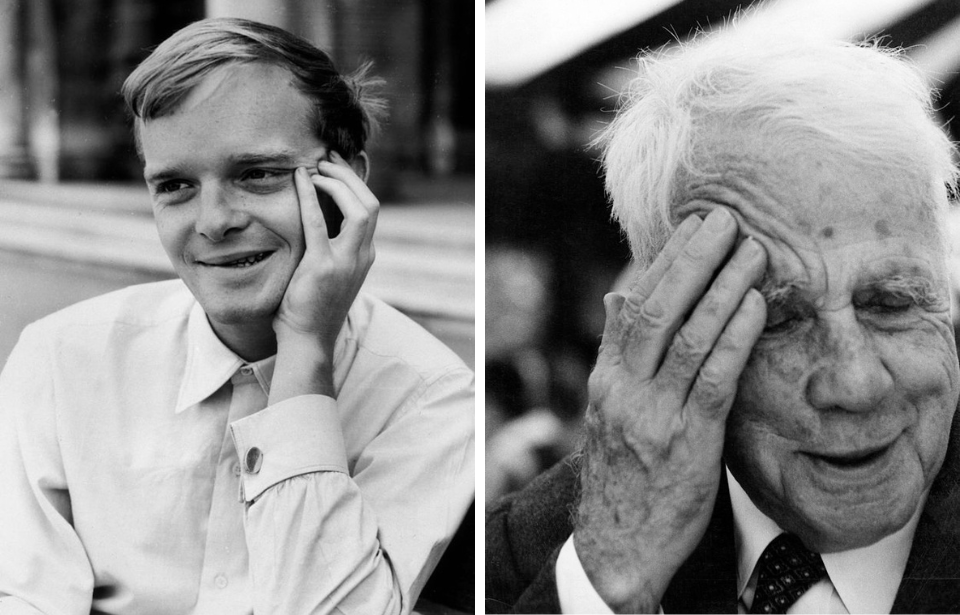

Frost and Capote couldn’t have been more different

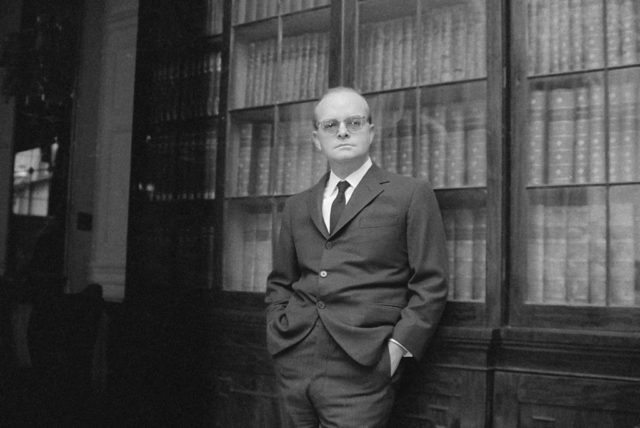

Truman Capote was born in 1924 in New Orleans, Louisiana, and was raised by grandparents and other older relatives for most of his childhood. His first successful short story, Miriam, was published in Mademoiselle Magazine in 1945. It received amazing reviews and even won an O. Henry Memorial Award.

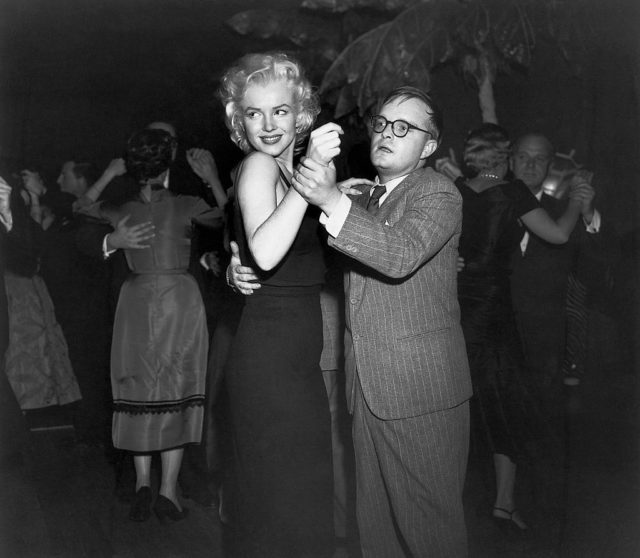

Much of Capote’s writing related to his own lived experiences like his haunting first novel Other Voices, Other Rooms. By the ’50s and ’60s, he had taken up an interest in journalism and non-fiction writing, like In Cold Blood – an account of a brutal 1959 Kansas murder – which appeared in an issue of The New Yorker in 1965. The celebrated author died in 1984.

Robert Frost couldn’t be more different from Capote. Born in 1874, Frost was a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and poet behind iconic poems like Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening, The Road Not Taken, and Birches. His poems often featured themes of nature, but many modern critics agree his work aligned closely with the classical style of the 19th century rather than the experimental and unique forms that challenged the status quo in the 20th century.

Unlike Frost, who died in 1963, Capote used controversial topics like sexuality in his writing and even pushed the boundaries of fiction and non-fiction with his journalistic-style novel In Cold Blood.

Capote and Frost’s tense encounter

Capote attended the annual Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 1944, an event that Frost helped to establish in the 1920s. Capote didn’t seem to have that much of an interest in the conference, calling it a “glob of all these old Midwestern ladies and librarians and whatnot, oohing and ahhing and carrying on.”

He then went on to explain how he planned to skip out on one of Frost’s poetry readings after coming down with the flu, but was convinced to attend after being told Frost was “furious” with the young writer for declining the invitation. Capote was present when the 70-year-old began his reading, until he tried to sneak out of the exit as he began to feel faint. In another interview, Capote said he bent down to scratch a mosquito bite on his ankle, making him look “slumped over.”

A journalist who observed the scene recalled that both scenarios were true. Capote did scratch his ankle, and then got stuck in the slumped-over position due to a “stiff neck.” Hoping to avoid looking like he had fallen asleep, Capote snuck toward the exit to make his escape, but not before Frost stopped his performance and threw his book at Capote!

Did Capote exaggerate the truth?

Frost added, “If that’s the way The New Yorker feels about my poetry, I won’t go on reading,” before storming out of the room. After the misunderstanding, Frost wrote an angry letter to New Yorker editor-in-chief Harold Ross about the disrespect he received from the young copyboy. Ross swiftly fired Capote, reportedly asking, “Who the hell is this Truman Capote, anyway?”

Capote did confirm Ross had hurled the pointed question at him but insisted he wasn’t fired after Ross was reminded that Capote had attended the event on his own time. Instead of being dismissed, Capote said he left the magazine for six months.

Actress Carol Matthau claimed that Capote told her an entirely different story. According to her, Capote was actually sent to review Frost’s poetry for The New Yorker and was fired as soon as he handed over his pointed, honest critique.

More from us: Exposing The Rich and Famous: Truman Capote and ‘La Côte Basque 1965’

For an acclaimed author, it seems like Capote couldn’t keep his story straight. Regardless of how it happened, both he and Frost remained cold toward each other.