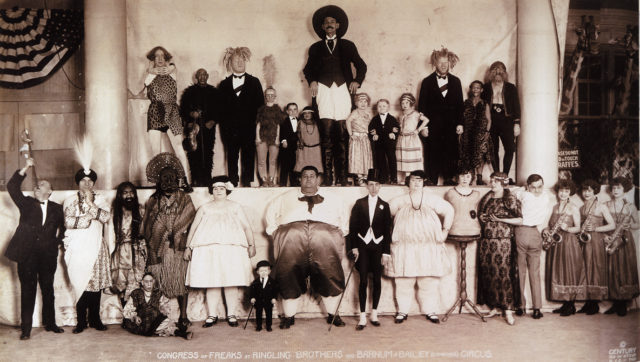

Before the age of television, circuses were a popular form of entertainment. People from far and wide would gather to witness death-defying acts and comedic performers, but the circus also has a dark side – quite literally. The “sideshow” was a secondary attraction at most circuses where attendees could view strange oddities and “freaks” – people born with disorders and disabilities who were often imprisoned and forced to perform.

Today, the way we perceive disabled people is very different from the 19th and 20th centuries. For people like Schlitzie, whose true name has been lost to history, many sideshow performers were forced to live their entire lives billed as a “pinhead” or “monkey girl” at the expense of others’ entertainment.

Who was Schlitzie?

Schlitzie’s true name, date of birth, location, and the name of his parents are unknown. However, his death certificate states that “Schlitzie Surtees” was born on September 10, 1901, in New York. He was born with microcephaly, a birth defect that left him with an abnormally small brain and skull, as well as a small stature and a severe intellectual disability.

He was said to have the cognition of a three-year-old. He was unable to fully care for himself and could only speak a few words and small phrases. Many of Schlitzie’s guardians (most of them unofficial) recounted that he could perform simple tasks but was able to understand most of what was said to him. He often reacted directly to a conversation and could even mimic those around him.

It’s not known exactly how Schlitzie ended up in the care of the circus, but by the early 20th century Schlitzie was a sideshow performer and part of a network of other microcephalic people who were billed as “pinheads” or “missing links.” Schlitzie often performed under titles like “The Last of the Aztecs,” “The Monkey Girl,” and “What Is It?”. Even though he was born a male, he was usually dressed in a muumuu and addressed with female pronouns to add to “shock value.”

Schlitzie performed for some of the biggest circuses in North America throughout the 1920s and ’30s, from Ringling Bros. to Barnum & Bailey.

From the circus to the cinema

In 1928, Schlitzie made his film debut in The Sideshow, a film set in a circus that featured real-life sideshow performers, but his big break came in 1932 when he was cast in Tod Browning’s horror film Freaks. Other sideshow performers starred in the film alongside Schlitzie, including “The Living Torso” Prince Randian, conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton, and Harry and Daisy Earles of The Doll Family – four siblings who all had dwarfism.

The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) film was based on a short story published in 1923, following a group of traveling French circus performers and a scheming trapeze artist who plans to seduce and murder a dwarf in the sideshow troupe to steal his inheritance. Schlitzie appears several times throughout the film, including in a scene with the film’s star Wallace Ford.

Freaks made headlines soon after its release, but the press wasn’t showering MGM with glowing reviews. Instead, audiences were shocked by the use of real sideshow performers. The film was even banned in the United Kingdom for 30 years.

The problem with ‘exploitation films’

In 1934, Schlitzie appeared in a controversial film called Tomorrow’s Children which is now considered to be an exploitation film, a movie that takes advantage of unknowing or unconsenting individuals at the expense of entertainment. Tomorrow’s Children takes a strong stance on the popular topic of eugenics, which many organizations – including the United States government – were in favor of at the time.

“Society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind,” Supreme Court Justice Wendell Holmes once wrote about eugenic policies. Tomorrow’s Children was set in the future where forced sterilization is used to achieve the genetic purity that was praised by the eugenics movement.

The film was a shocking clap back to the supporters of eugenics, which included a majority of Americans. This would all change when German Socialists used the same ideologies as the American eugenics movement to legitimize the mass murder of Jewish people in World War II.

Schlitzie was unfortunately wrapped up in the matter when he was cast to play one of the people forced to undergo sterilization because of his disability. While politics and knowledge of disabilities were different in the 1930s, it is clear today that Schlitzie was unable to consent to any of the acting or sideshow performances he was essentially forced to do.

Not only had the world alienated him for being different, but they also used him as the butt of countless jokes and manipulated his identity to make more money off of an unwitting person – money he likely never saw.

What happened to Schlitzie?

In 1936, a chimpanzee trainer named George Surtees adopted Schlitzie and became his legal guardian, a figure the 34-year-old had likely not had in any official capacity before.

Schlitzie continued to perform in sideshows until Surtees’ death in 1965. Surtees’ daughter committed Schlitzie to a Los Angeles hospital until Bill “Frenchy” Unks – a sword swallower and circus performer – recognized Schlitzie on a visit to the hospital. Unks said that Schlitzie seemed to miss the carnival, and that being out of the public eye had made him depressed. Ultimately, Schlitzie was discharged from the hospital and put in the car of Unk’s circus employer, Sam Alexander.

Schlitzie performed in the sideshow for Alexander until 1968. Following the end of his circus career, Schlitzie retired to Los Angeles where he occasionally performed on the sideshow circuit, even traveling to Hawaii and London, England. Between shows, he was a popular Hollywood street performer often accompanied by caretakers selling souvenir pictures from his circus days. One of his favorite spots was Santa Monica Boulevard, close to a local park where he loved to feed the pigeons and ducks.

More from us: Circus Facts That Perfectly Explain These Unsettling and Eye-Catching Vintage Photos

On September 24, 1971, Schlitzie died at the age of 70. This was a relatively long life for someone with microcephaly. He is buried at the Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Rowland Heights, California.