Whimsical outfits, pointed hats, juggling, and crude jokes are things that identify and define a medieval jester, right? Well, yes, on special occasions, but that is only part of the reality for the medieval jester. There were so many other facets of their lives and expectations of their behavior that went far beyond simply “entertaining.” In fact, a medieval jester was often put directly in the face of danger. Although this job has largely died off over the centuries, the argument could be made that there are current-day jesters in the form of entertainers.

The true role of the medieval jester

The term “jester” wouldn’t be introduced until the 16th century. The men and women who performed the role of jesters were originally called minstrels, meaning “little servants.” It was during the 12th century that the term “fool” came to represent the role of the jester. However, these terms encompassed people with many different talents, including singers, musicians, jugglers, and more.

We think of a medieval jester as the court entertainment, acting foolishly and clumsily for the enjoyment of the king and queen. In some instances, yes- this kind of situation would occur. In reality, however, the jester could take on many different roles depending on their own personal talents. Plus, if a jester had more than one skill, they were seen as far more valuable and entertaining than one with only a single talent.

Throughout the Middle Ages and the Tudor period, jesters wore many hats (pun intended). Feasts and festivals were not held by their courts every day, so a good portion of the work jesters needed to fulfill had nothing to do with entertaining their noblemen. Instead, they’d have to contribute to the chores of the household. This could include tending to the hounds or other livestock, completing the household shopping to feed the residents and their servants, keeping inventory of all of the food in the household, and delivering messages and mail on behalf of their noblemen.

The three types of medieval jesters

Medieval jesters could be classed into three categories – “Licensed Fools,” “Natural Fools,” and members of “Fool Societies.” Though they all served essentially the same purpose, they had distinct differences from one another. Across the three categories, those who possessed physical deformities, such as a limp or humpback, as well as dwarves, were considered top-tier jesters.

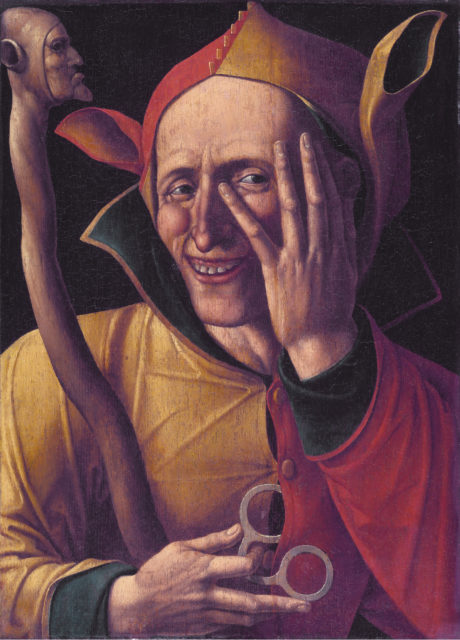

The Licensed Fool could also be called a professional jester. This type of jester was employed by a nobleman from a high court, lived on the premises, and helped to take care of the residence. They were usually quick-witted, educated and intelligent, and often talented at many things. When they performed for the court, they wore the classic jester outfit, including bright, colorful costumes of whimsy and the iconic hat that is modeled after donkey ears. When they weren’t performing, they generally kept their employer and the rest of the household in good spirits and wore normal clothing.

The Natural Fool was also known as the innocent jester. These were people who displayed some sort of mental illness or abnormality that was believed to be naturally “entertaining.” Those who were employed as innocent jesters didn’t really have to perform in a traditional sense. They were almost kept as pets by the noblemen who “employed” them, though they typically would not receive any money. Instead, their pay came in the form of food, clothing, and shelter. Innocent jesters were most appreciated for their tendency to always speak the truth.

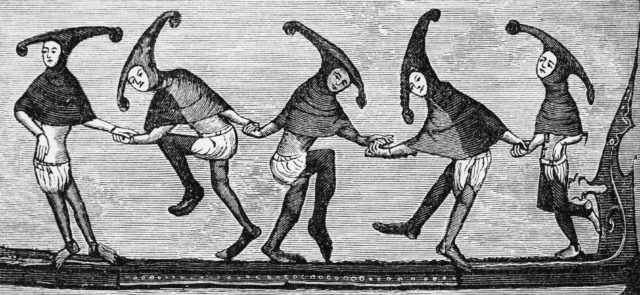

Members of the Fool Societies were amateur jesters who would take to the streets during festivals and holidays to perform. They were hired in groups and traveled from city to city, often employed to perform acrobatic stunts. They would dance through the streets and entertain the residents of the city. Fool societies became particularly popular in France.

‘Don’t kill the messenger’ has an unexpected meaning

For medieval jesters who worked directly for noblemen, one aspect of their work put them in the face of danger. When different medieval groups went to war with each other, jesters were brought to help keep morale high before battle. When the two armies lined up to face one another, the jester would march up and down between them, entertaining the soldiers to calm their nerves. They would sing, make jokes, and insult and mock the opposing army.

In this way, the medieval jester was also used as a type of psychological warfare that taunted the enemy. They would juggle swords and lances in front of them, degrade their physical stature and otherwise cause enemy soldiers to get angry. Enemies who could not control their temper would prematurely charge at the jester, breaking their line and weakening their defenses.

During battles, medieval jesters would also assume roles as messengers. They were required to carry messages back and forth between the warring leaders, and their safety often depended on the contents of the message and the temper of its recipient. The messages they carried were usually terms of release for prisoners or demands for surrender. If the opposing leader was offended by the contents of the message, they would sometimes take it out on the poor jester who was just doing their job.

To the enemy, the jester was just a disposable servant. In cases where they were offended, they used the jesters to serve as their response to whatever demands were made and as an example of their power. They would “kill the messenger” and catapult the body back to their own side. In some cases, if the opposing leader was insulted enough, only the head of the jester would be hurled back to their camp.

How were medieval jesters paid?

Medieval jesters were paid differently depending on the kind of service they provided. Court jesters had a very different lifestyle from traveling jesters, and it reflected on their income. A court jester was given a permanent place of residence in the home of the nobleman they served. They were paid handsomely for their services and were in some cases given a secured retirement in the form of land.

Tom the Fool was the jester who performed at the marriage feast of King Edward I’s daughter, Elizabeth. For his performances, he was provided a fee of 50 shillings. In those days, that was an absolute fortune. Roland le Petour, who was the court jester of King Henry II, was gifted 30 acres of land upon his retirement. The only stipulation was that he return to the court every year on Christmas Day to “leap, whistle and fart.”

However, most jesters were not lucky enough to score a gig in the court. In fact, most jesters were traveling ones with no permanent residence. They lived in poverty and survived on the little money they made from whatever jobs they could find.

Maggoty Johnson, the last professional jester

Although being a jester was a popular job during the Medieval period, it did not withstand the changing times in its traditional forms. Today, comedians and entertainers are likened to medieval jesters, but their roles are vastly different.

One of the last professional jesters was Samuel Johnson, better known as Maggoty Johnson, who was born in 1691. He found work in some of the wealthiest houses in England, and his crowning achievement was his production of Hurlothrumbo, which was made possible by his patron, the Duke of Montagne. Hurlothrumbo was a play that ran for 30 nights in London. Maggoty wrote it, casting himself in the lead role. He took this project very seriously.

More from us: Life in a Medieval Castle Was Gross. Actually, It Was Grosser Than You Think.

Maggoty Johnson retired in his 50s and ultimately died at the age of 82. He was originally buried at a churchyard but was reburied in a wooded area as per his living request. The location of this last jester’s grave has since been named Maggoty Wood, and is said to be haunted by Maggoty’s ghost.