Our obsession with true crime isn’t a new one. In fact, it was a major source of entertainment in the 1920s. With the new freedom the jazz age brought and the dangers of smuggling during Prohibition, it’s no wonder that some turned to the most unique approaches to criminal justice.

But one woman in California takes the cake for the most outlandish plan to get criminals to confess their crimes.

The skeleton patent

Helene Adelaide Shelby thought of a way to increase the effectiveness of criminal interrogations without the need for detectives to coax out the truth. Not much is known about the woman behind the invention, but we do know she was a relatively well-off California resident who made her money in real estate, with properties in Oakland, Santa Cruz, and San Francisco.

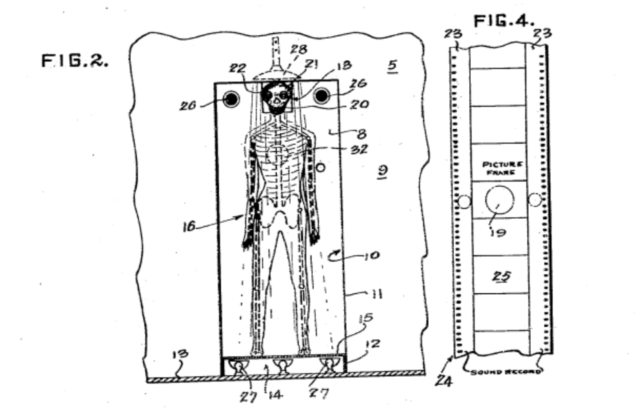

Shelby died in 1947, leaving behind her husband Edgar and the unusual design as her one and only invention. A US patent was filed by Shelby in 1927 for an “Apparatus for obtaining criminal confessions and photographically recording them.” The apparatus in question was a large skeleton with glowing red eyes and a camera hidden inside.

“It is a well-known fact in criminal practices that confessions obtained initially from those suspected of crimes through ordinary channels, are most invariably later retracted,” Shelby wrote in her patent application. By using the skeleton apparatus, Shelby hoped investigators could “produce a state of mind calculated to cause [a criminal], if guilty, to make confession thereof.”

How does it work?

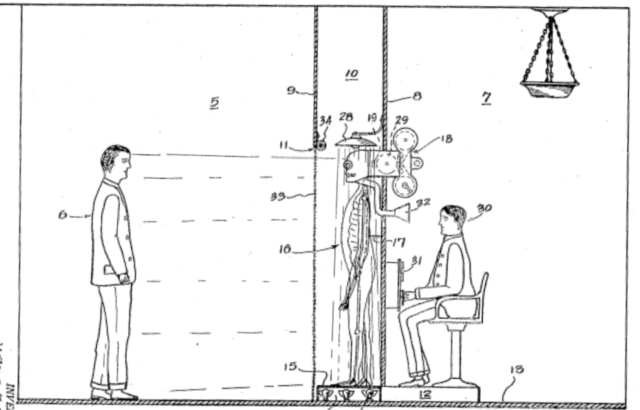

How exactly does a skeleton elicit a confession? Shelby’s process is surprisingly thorough. The suspect is confined in a small, dark room while the investigator sits in a second, adjoining room. Questions are asked through a microphone as a curtain lifts up to reveal the skeleton illuminated by “a plurality of lights.”

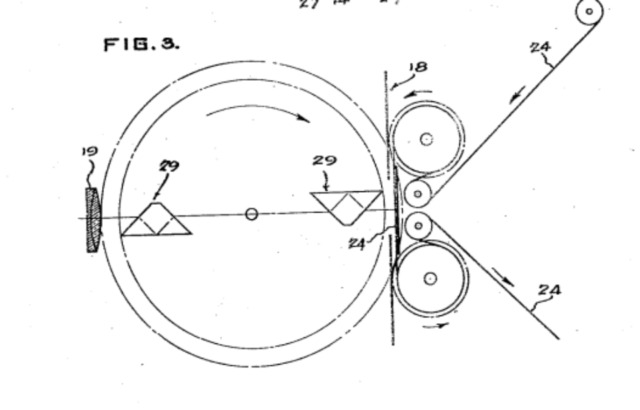

The goal was to make the skeleton appear to be an apparition that miraculously materialized before the suspect, appealing to one’s fears of the supernatural. The skeleton’s eye sockets contain red lightbulbs to give it an “unnatural ghastly glow” while the speaker connected to the microphone is pointed right out of the skeleton’s mouth.

As the suspect confesses to the ghostly figure, a camera in its skull records everything in photos and audio recordings. The recordings could be replayed in court as evidence. If this sounds unethical to you, your instincts are correct! Luckily, the Supreme Court ruled in 1961 that coerced confessions – whether to a skeleton or a human – are not admissible evidence in court after the Rogers vs. Richmond case.

What happened to Shelby’s idea?

The skeletal confession chamber reflects the beliefs of the ’20s and ’30s when movements like Spiritualism took off – coinciding with the temperance movement and subsequent prohibition of alcohol. Spiritualists who claimed they could converse with the dead often used similar contraptions to give the illusion of a profound, supernatural experience.

More from us: The Unsolved Murder Mystery That Helped Start America’s True Crime Obsession

Helene Adelaide Shelby died in 1947, precisely 20 years after she submitted her patent application. And while the patent was approved, there is no evidence to suggest it was ever used to draw out a criminal confession.