The Antebellum period is often remembered as a romantic era that celebrates the beauty of the South, grand plantation estates, and the classic “southern belle” style of Scarlett O’Hara. The reality of life in the Antebellum south was far from idyllic. Marked by a turbulent change in the politics of slavery and the division of American ideals, this period has a fascinating and misunderstood history.

What was the Antebellum period?

The Antebellum period gets its name from the Latin phrase ante bellum, or “before the war.” As early as 1815, slavery was quickly becoming its own economy in the Deep South, and with it, a new culture was born. Prior to 1815, slavery was seen as a temporary system used to build the still-young American nation but as the 19th century progressed many slave owners began to see the plantation economy was not only a means to an end, it was a goldmine.

In the 18th century, the Transatlantic slave trade brought enslaved Africans to the American south to be used as free labor in agriculture. By 1790, nearly 700,000 enslaved persons were living in the United States, roughly 18 percent of the US population. That number would grow to over three million by 1850.

The economics of the slave trade

When Eli Whitney, owner of the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, invented the cotton gin – a device that quickly separates the cotton fibers from the seeds of the plant – slavery became immensely profitable. Between the free labor of slaves and the innovation of the cotton gin, the plantation system grew into a massive economy that supplied 75 percent of the world’s cotton.

Around the same time, the US would declare war on Britain, triggering the War of 1812. Tensions between Britain and America led to the blockade of the Atlantic seaboard, stopping the slave trade but driving Americans to rely on domestic production and agriculture instead of imports from Europe.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 suddenly freed up vast swaths of land in the Deep South previously occupied by Indigenous peoples. Americans purchased the land for cheap and turned the fertile soil into cotton, tobacco, and sugarcane plantations. Slaves were purchased by plantation owners to work the land, and since the importation of slaves was banned in 1807, having a free workforce that simultaneously produced new slaves through childbearing solidified the plantation system.

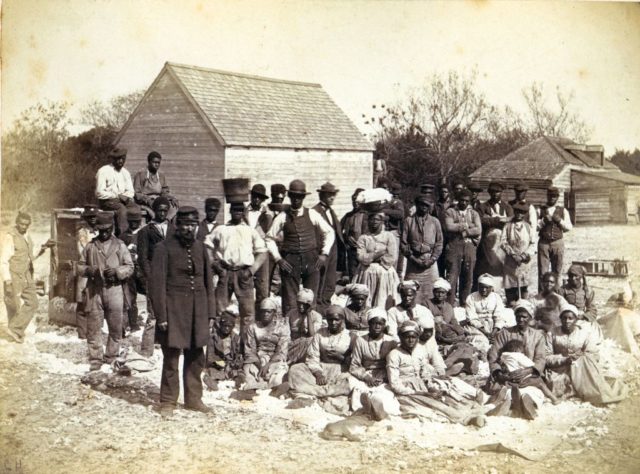

Soon, wealth wasn’t shown through the amount of money you had or how large your house was, it was defined by the number of slaves you owned. The plantation system enacted violence against enslaved people for decades, not only through forced labor but also through corporal punishment, abuse, and neglect.

The horrific experiences of slavery

Slaves working in the Deep South had many different lives than those in the North. While slaves worked in both areas, enslaved people in the North typically worked indoors as servants to the wealthy and powerful. Slaves in the South worked long and grueling hours in the fields with little time off. All slaves in America were denied rights – they weren’t even seen as human, just as property.

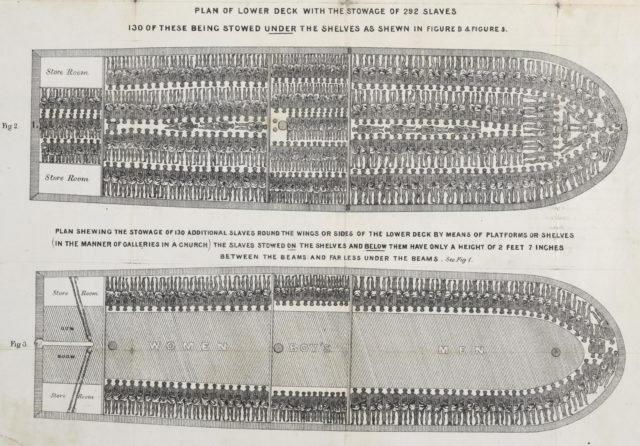

People from Africa and the West Indies were taken from their homelands and forced onto ships bound Westward. One narrative recorded by a slave named Olaudah Equiano details the horrific conditions of the slave trade:

“The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time… This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.”

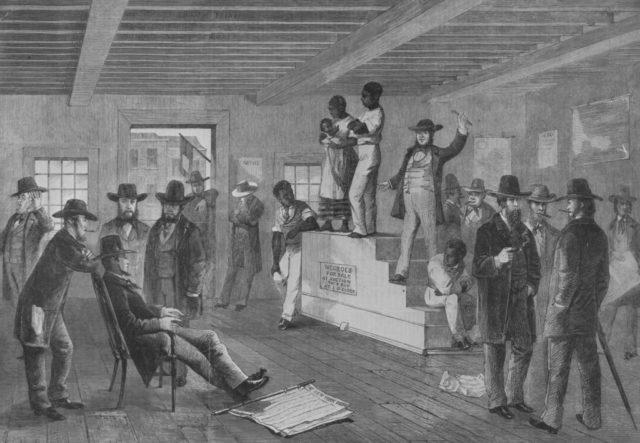

Once captured slaves arrived in America, they were sold to owners and officially became property – a process known as chattel slavery. Men and women would pick cotton or harvest sugarcane for hours on end, often without breaks – even in the most extreme circumstances. James Lucas, a former slave in Mississippi born in 1833, recalled the day he was born:

“I was born in a cotton fiel’ in cotton pickin’ time, an’ de wimmins fixed my mammy up so she didn’ hardly lose no time at all. My mammy sho’ was healthy. Her name was Silvey an’ her mammy come over to dis country in a big ship. Somebody give her the name o’ Betty, but twant her right name. Folks couldn’ un’erstan’ a word she say. ”

Another enslaved woman, Louisa Adams, described her upbringing in the slave quarters of North Carolina:

“We lived in log houses daubed with mud. They called ’em the slaves houses. My old daddy partly raised his chilluns on game. He caught rabbits, coons, an’ possums. We would work all day and hunt at night. We had no holidays. They did not give us any fun as I know. I could eat anything I could… My brother wore his shoes out, and none all [through] winter. His feet cracked open and bled so bad you could track him by the blood.”

As property, enslaved people were bought and sold regardless of their family ties. Mothers would be separated from their children, siblings were taken away from siblings, and even entire generations were pulled apart. Many generations of children were born into slavery, creating a continual cycle of trauma and violence.

The start of the abolition movement

In the lead-up to the Civil War, a growing concern over the ethics of slavery led to the abolition movement. Historian James M. McPherson described what it meant to be an abolitionist in his book The Struggle For Equality: “one who was before the Civil War had agitated for the immediate, unconditional, and total abolition of slavery in the United States.” To McPherson, anti-slavery and abolition were not one and the same.

Northern states began to ban slavery following the American Revolution, with Vermont being the first to abolish slavery in 1777, and Pennsylvania followed not far behind in 1780 under the guidance of Benjamin Franklin. By 1804, all Northern states had abolished slavery – though many people were still enslaved for years – while the South’s slavery industry was picking up momentum. By the 1830s, abolitionist societies and publications appeared throughout the United States, and by 1840 more than 150,000 people were members of abolitionist organizations.

Slavery dwindled throughout most of America except for the plantations of the Deep South, where cotton, sugar, and other crops were booming. As abolition became more popular in the North, the South made it illegal. Even carrying abolitionist publications, which pacifist minister Amos Dresser did in Nashville, Tennesee, lead to a public whipping.

Everything came to a head when Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860. Slave owners of the South knew that sweeping abolitionist legislation was bound to happen under Lincoln’s leadership, so they decided to protect their empires by separating from America to create their own country where slavery and the dream of the Antebellum years would be upheld. The American Civil War had begun.

The Civil War and the end of the Antebellum period

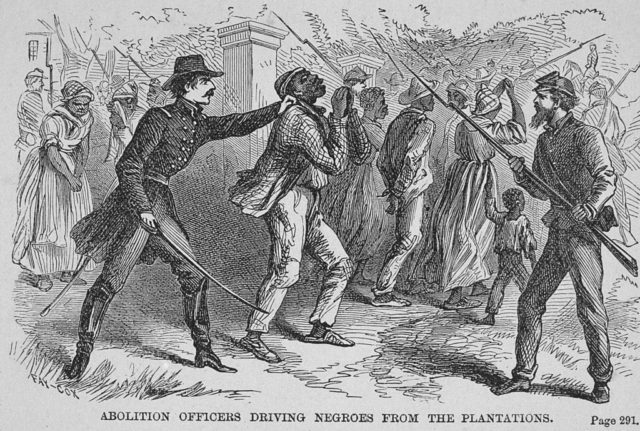

Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862, which abolished slavery in Washington D. C. Around the same time, Congress passed the Confiscation Acts. These measures declared escaped slaves from the South to be confiscated war property so they could legally be protected from being returned to their masters in the Confederacy.

As battles between the Union and the Confederacy continued, Lincoln continued to move forward with abolition. In 1863, following the Union victory at Antietam, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all enslaved people living in the Confederate states on January 1, 1863. With the primary labor force of the Confederacy gone, their defenses were weakened. Meanwhile, thousands of emancipated Black men joined the Union Army to fight against their former masters and oppressors.

General Robert E. Lee surrendered to the Union on April 9, 1865. Just days later, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Seven months after the Confederate surrender, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took effect, officially ending slavery. Even though slavery was legally over, abolition wasn’t so black and white. The system of slavery took many years to construct, and it would take even longer to dismantle.

The Antebellum period has been heavily romanticized in recent years. While the slave quarters, fields, whips, and chains have long been wiped from plantations, grand historic estates still stand completely devoid of the history of bloodshed they once represented. There are roughly 375 plantation museums across the United States, each with varying degrees of historical representations of slavery – though some have none at all.

More from us: Why Are People Still Partying on Plantations?

By removing the history of slavery from the artifacts of the antebellum period, we are perpetuating the same level of ignorance that allowed slavery to continue for nearly 100 years – which cost thousands of lives, ruined families, alienated people from their homes and cultures, and created an ongoing cycle of generational trauma that many are still working to overcome.