The “call of the void” is a simple yet complex phenomenon when the human mind seems to sabotage itself for a split second before rational thinking kicks in. It may sound like an unusual occurrence, but a lot more people experience it than you might expect. Numerous professionals have come to their own conclusions as to why the call of the void happens to some of us, but there are no conclusive answers yet.

The ‘call of the void’ describes intrusive thoughts

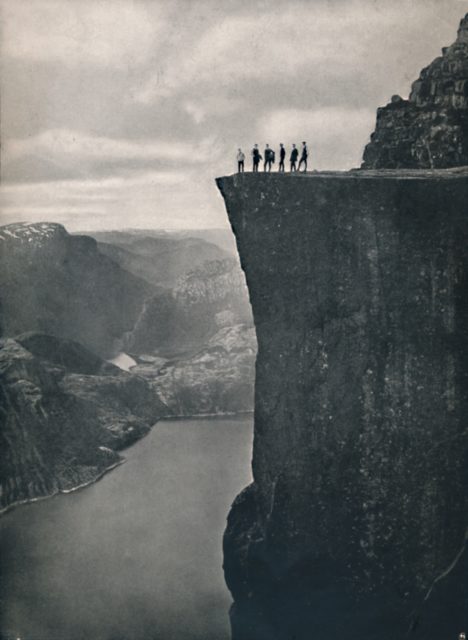

If you’ve ever been standing in a high place, like on a cliff or a bridge, and you’ve thought to yourself, “what if I jumped?” but didn’t actually do it or want to do it at all, then you’re not alone. A lot of people have experienced those same kinds of thoughts, and although there is no definitive explanation as to why it happens, the name for it is the “call of the void.” The French term is l’appel du vide, and it describes more than just thinking about jumping from high places.

The call of the void is considered part of a larger genre of thinking known as “intrusive thoughts.” These thoughts are unwanted and involuntary and can happen to just about anybody, anywhere, and are reckless impulses to do something that could be anywhere from mildly to extremely self-destructive. Other examples of intrusive thoughts include swerving your car into oncoming traffic or screaming at the top of your lungs in a library.

Many people believe that the call of the void is linked to thoughts about ending one’s life. However, research on those who end their lives has suggested that it is not an impulsive decision, but rather a drawn-out and highly contemplated process. The call of the void is not a death wish, but due to the nature of the intrusive thoughts, not many people are willing to talk about it.

A comprehensive study tried to explain why it happens

One of the most comprehensive studies pertaining to the call of the void was conducted in 2012 by Jennifer Hames, April Smith, and others at the Department of Psychology at Florida State University. In this study, 431 undergraduate students were asked to complete online questionnaires asking if they’ve ever experienced the call of the void. In the study, they referred to the feeling as the “High Place Phenomenon” (HPP).

While the study focused on each individual’s experience with the call of the void, it also monitored their mood behaviors, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and levels of ideation. In this sample, about a third of the participants admitted they had at some point experienced intrusive thoughts linked to the call of the void. Of that third, just over 50 percent said they have never had end-of-life thoughts.

Additionally, of those who felt they had experienced the call of the void, those with higher anxiety levels were found to have higher rates of end-of-life thoughts. Higher ideation rates were linked with more frequent urges, suggesting that people with anxiety experienced the call of the void more frequently.

The results were telling, but the study was flawed

Following the survey, the study concluded that “The HPP is commonly experienced among [end-of-life] ideators and non-ideators alike. Thus, individuals who report experiencing the phenomenon are not necessarily [hoping for death]; rather, the experience of HPP may reflect their sensitivity to internal cues and actually affirm their will to live.” The study basically suggests that the call of the void is not one’s urge to end their life, but is rather a strange way of wanting to stay alive.

As the study explains, it may be a mix of the conscious and unconscious mind at play. Smith explained this conclusion, saying, “It could be the case that when you’re up somewhere high, your brain is basically sending an alarm signal — you know, be careful. And that could actually lead you to take a step back, or notice your surroundings. Then that more deliberative process kind of kicks in and you start to think, why did I just take a step back? I’m totally fine. There’s no reason for me to be afraid. Oh, I must have wanted to jump.”

By jumping away, a person may think that they must have wanted to jump in the first place (the unconscious mind). However, by jumping back, they made the decision to live because they do want to live (the conscious mind). If it sounds confusing, that’s because it is.

Ultimately, the study is flawed. It used a very small sample size and only surveyed undergraduate students. This does not serve as an inclusive representation of the larger population. As well, the link between the call of the void and anxiety or life-ending thoughts was only superficially explored and therefore the conclusions of the study cannot be considered decisive.

Other philosophers have weighed in on the call of the void

Not everyone equates the call of the void with a person’s appreciation of life and their will to live, as the 2012 study suggests. Cornell University cognitive neuroscientist Adam Anderson believes the call of the void is a defense mechanism that can be explained through a gambling analogy.

As explained by oddfeed, “Consider this scenario: you visit a casino and immediately begin to lose money at a blackjack table. You are so afraid of continuing to lose that you actually begin to gamble higher and higher stakes on each hand.” Your fear of losing the next hand is more immediate than the loss of money that will follow, so you keep betting higher and higher amounts to avoid losing. In this way, the immediate danger of the cliff you are standing on is then met with the natural brain signal to overcome that immediate danger by stepping into it, despite possibly falling to your death.

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre described the call of the void as “a moment of Existentialist truth about the human freedom to choose to live or die.” Sartre’s ideology explains that humans are equally as capable of doing bad things as they are doing good. The only difference is in the boundless choices they make. As humans are confronted with an endless amount of choices, they naturally become overwhelmed and begin to call into question their existential identity. Then, their thoughts turn to the innately human thought of sabotaging one’s self.

More from us: Investigation of a Masterpiece Reveals Incredible Secret Hidden for 100 Years

If there’s anything we’re taking away from these theories, it’s that at least we’re not the only ones who experience the call of the void.