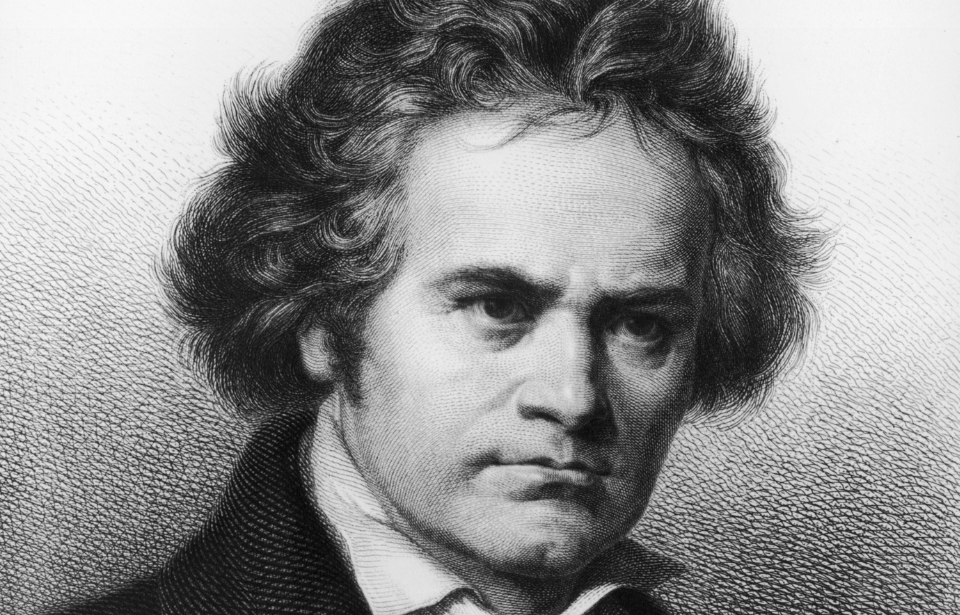

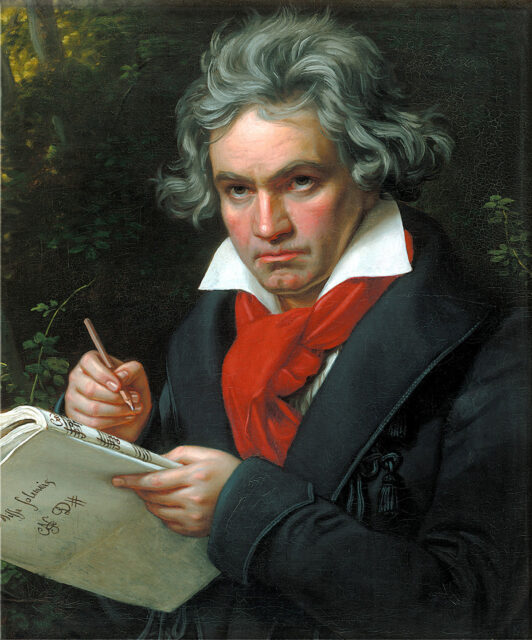

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of the most famous composers in Western music history. Composing such renowned works as his fifth symphony, Moonlight Sonata, and Für Elise, Beethoven’s music is known the world over. From concert halls to movie screens, his compositions have graced ears for generations.

Instantly recognizable, even if you haven’t purposely set out to listen to his music, Beethoven has become so entrenched in society that most people have heard at least one of his compositions whether they realize it or not. Beethoven’s music may be extremely well known, but there is still much to learn about the man behind the melodies.

DNA taken from locks of Beethoven’s hair has been analyzed by researchers. Amazingly, they’ve discovered secrets about the composer’s health, death, and family.

Who was Beethoven?

Beethoven was born sometime in 1770 in Bonn, Germany. An exact date is unknown, however, we know that he was baptized on December 17, 1770. He started music early on with intense lessons from his father, Johann van Beethoven, and later, Christian Gottlob Neefe, a composer who oversaw Beethoven’s first composition.

In 1787, he went to study with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Vienna. Mozart was greatly impressed by Beethoven and was said to have told some of his friends that “this young man will make a great name for himself in the world.”

Beethoven did just that, and following his first composition at the age of eleven in 1782, came symphonies, concertos, string quartets, piano sonatas, and operas. Over the course of more than forty-five years, Beethoven composed 722 works.

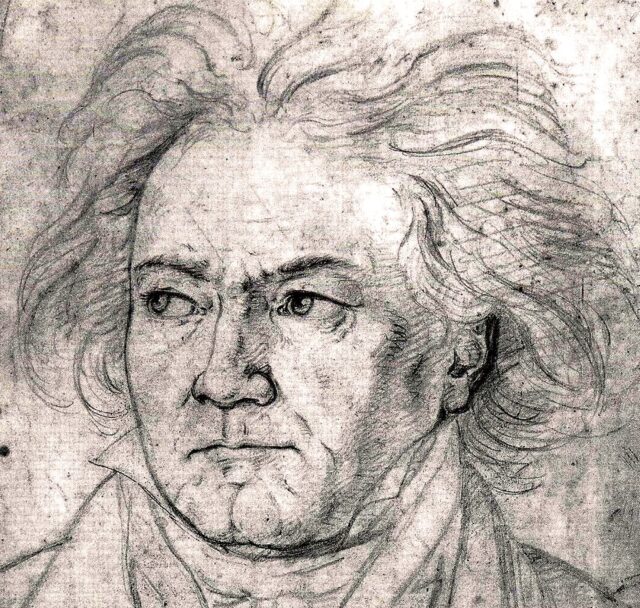

Beethoven’s health

During his life, Beethoven suffered from many illnesses. Beginning in his mid-to late-20s, Beethoven suffered from a loss of hearing. This slowly worsened and eventually led to him being completely deaf by 1818. The composer also suffered from gastrointestinal problems. He suffered two attacks of jaundice, a symptom of liver disease.

On March 26, 1827, Beethoven died at 56. Following his death, an autopsy was performed. This procedure confirmed that Beethoven’s cause of death was cirrhosis of the liver. Since 1827, debate has surrounded the causes of his death. Only now with research on his DNA can we begin to see genetic explanations for his poor health and his eventual death.

The key to Beethoven’s secrets – hair?

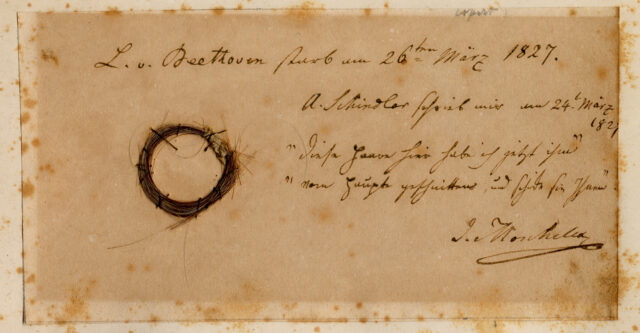

Eight locks of hair were analyzed. These samples were taken from both public and private collections in Britain, Europe, and the United States. Five were determined to be from Beethoven. These all had the same DNA, and were from a male of European descent. A sixth sample did not yield enough DNA for analysis, and two more were found to be from other people.

One of the two confirmed to not be Beethoven’s was actually a famous sample said to have been owned by Ferdinand Hiller. A student of Beethoven’s, Hiller was 15 when the composer died. Following his death, Hiller was said to have taken a lock of Beethoven’s hair. Despite this story, the sample has now been confirmed as a lock of a woman’s hair.

Previous research had been conducted on the “Hiller lock.” This found that its owner had suffered from lead poisoning. With this new research indicating that this sample was not actually Beethoven’s, those original findings are no longer relevant to his story.

One sample, which was confirmed to be Beethoven’s, was actually hand delivered by the composer to pianist Anton Halm in April 1826. It was attached to a note which said “Das sind meine Haare!” (“That is my hair”).

Another sample, known as the ‘Stumpff Lock,’ was confirmed to be Beethoven’s due to its connection to people living in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Combing through the data

The results of the tests found no genetic factors relating to Beethoven’s loss of hearing nor his gastrointestinal issues. They did find, however, genetic risk factors for liver disease as well as evidence of a Hepatitis B infection, which would have occurred in the final months of his life.

Tristan Begg, the study’s lead author at the University of Cambridge, said: “we can surmise from Beethoven’s ‘conversation books’, which he used during the last decade of his life, that his alcohol consumption was very regular, although it is difficult to estimate the volumes being consumed.”

Beethoven’s contemporaries saw little wrong with his alcohol use, however, compared to today’s standards, these were likely very high quantities to be consuming. Begg added, “if his alcohol consumption was sufficiently heavy over a long enough period of time, the interaction with his genetic risk factors presents one possible explanation for his cirrhosis.”

Beethoven’s Hepatitis B likely contributed to his liver cirrhosis. This cannot be confirmed, but there is cause for speculation.

Untangling a family mystery

A Beethoven family mystery was also discovered. While analyzing Beethoven’s DNA, it was compared to five men living in Belgium – all with the last name Beethoven. It was found that the composer’s DNA showed a different Y-chromosome than the one that all five Belgium Beethovens shared. This was evidence that a child on Beethoven’s father’s side was actually from an extramarital relationship.

The study suggested that this occurred sometime between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in c. 1572 and that of Ludwig van Beethoven in 1770. The exact generation when this took place, however, cannot be determined.

The final cut

Nothing was found relating to Beethoven’s hearing loss or gastrointestinal problems. However, this research better helps us understand genetic factors contributing to the composer’s death, as well as a family mystery that Beethoven himself didn’t know anything about. Scientists from across the field have praised the paper and its results.

More from us: Famous Musicians With Equally Famous Musician Children

As Tristan Begg said: “We hope that by making Beethoven’s genome publicly available for researchers, and perhaps adding further authenticated locks to the initial chronological series, remaining questions about his health and genealogy can someday be answered.”