Groundbreaking inventions have driven civilization forward, revolutionizing the way we live. That being said, behind the scenes of these progress and technological advancements, are some tales of tragedy. Some of these brilliant inventors, consumed by their passion for discovery and driven by a desire to push boundaries, have tragically met their untimely demises as a direct result of their own creations.

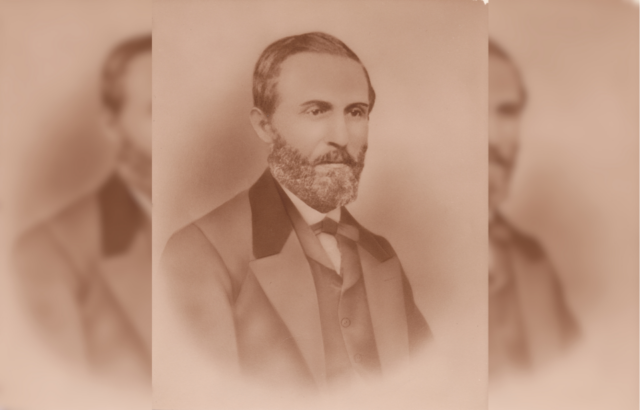

William Bullock

William Bullock was an American inventor. Born in Greenville, New York, he moved to Savannah, Georgia, at the age of 21 and opened a machinery shop. While working at his shop, he devised a shingle-cutting machine. Unable to market his invention, he sold his business and moved back to New York.

He would go on to invent or make improvements to various machines, including the cotton and hay press, lathe cutting machine, and seed planter. In 1849, his grain drill won a prize from the Franklin Institute. After this, he turned his attention to journalism, becoming an editor for The Banner of the Union, a Philadelphia newspaper. While working for the newspaper, he improved upon the rotary press that Richard March Hoe had invented in 1843.

Bullock’s improvement made for a less laborious process, but it would also lead to his death. On April 3, 1867, while making adjustments to one of his presses, he attempted to kick a driving belt onto a pulley. Bullock’s leg was ultimately caught in the machine and crushed. In the following days, the leg developed gangrene, and on April 12th, he died during the operation to amputate his destroyed leg.

Thomas Midgley Jr.

Thomas Midgley Jr. was an American mechanical and chemical engineer. Two inventions that he played a significant role in the creation of were leaded gasoline and Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which are popularly known in the United States as Freon. Both of these creations have become known for their horrible impact on the environment, which has led him to be described, as one author put it, as a “one-man environmental disaster.”

In 1940, at the age of 51, Midgley contracted polio. He was ultimately left disabled and bedridden. At his home in Worthington, Ohio, he created a whole system of ropes and pulleys, which would allow him to get out of bed without the help of others. On November 2, 1944, Midgley was found dead. In an attempt to get out of bed, he had gotten caught in the ropes, which caused him to die of strangulation. He was 55 years old.

Midgley’s death has publicly been described as an accident, however, many believe that he intentionally took his life.

Stockton Rush

Stockton Rush is the most recent addition to the list. Co-founder and chief executive officer of the deep-sea exploration company OceanGate, Rush was the submersible pilot who controlled Titan on the expedition to the wreck of the Titanic, which saw the death of all five people onboard after the sub imploded.

Rush played a role in the development of the submersible on which he met his demise. The Titan was made of carbon fiber and titanium and carried various cameras and scanners, as well as a life support system with enough oxygen for 96 hours and a real-time health monitoring system. The sub also had a lot of elements that weren’t purpose-built, including a $30 Logitech F710 game controller for steering.

Numerous safety issues had been brought up, some by David Lochridge, the director of marine operations for OceanGate, and others by different organizations including the Marine Technology Society. In regards to these and other concerns, Rush said, “At some point, safety just is pure waste. I mean, if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed. Don’t get in your car. Don’t do anything.”

Karel Soucek

Karel Soucek was a Czech professional stuntman living in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. On July 2, 1984, Soucek performed the classic daredevil stunt of going over Niagara Falls in a barrel he had custom-built for himself. He prepared for the performance by sending unmanned barrels over the falls, testing currents, and also testing his barrel’s shock absorbency. Soucek’s homemade barrel was nine feet long and five feet wide.

The barrel was painted red and was emblazoned with the words, “Last of the Niagara Daredevils – 1894” and “It’s not whether you fail or triumph, it’s that you keep your word… and at least try!” Try, he did. On July 2, 1984, the barrel with Soucek in it entered the Niagara River about 1,000 feet from the falls. In only a matter of seconds, the barrel went over. Soucek survived the stunt but suffered a few cuts and bruises.

Soucek was fined $500 for not having a license to perform the feat. That was little compared to the $15,000 he had spent on materials and labor to build his barrel and $30,000 to film it. Enjoying the success of his first exploit, he looked to his next adventure: a 180-foot barrel drop from the top of the Houston Astrodome into a tank of water.

On January 19, 1985, Soucek, in his barrel, was dropped 180 feet above a tank of water. The barrel began spinning, and instead of landing in the center of the water tank, it hit the rim. Soucek was still alive directly following this stunt but ultimately died.

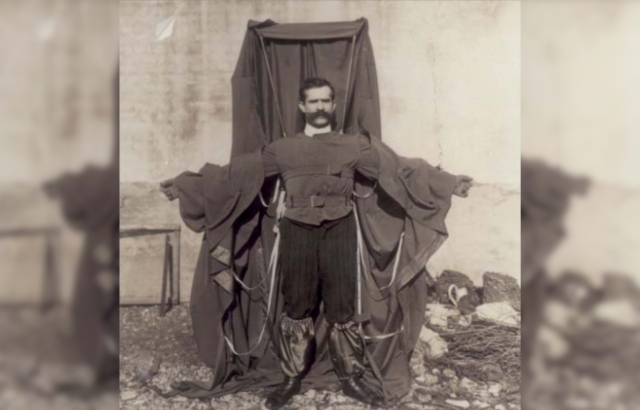

Franz Reichelt

Franz Reichelt was an Austro-Hungarian-born French tailor who also tried his hand at inventing. In July 1910, he started the development of a parachute suit. It had the overall appearance of a bulkier version of a pilot’s flight suit, and with extra silk panels and metal rods, Reichelt hoped that it could act as an effective parachute for pilots or other adventurers at low altitudes.

Reichelt announced in February 1912 that he would show off his invention with a test at the Eiffel Tower. He arrived at the tower on Sunday, February 4th, at seven in the morning. Journalists were present to report on the outcome of the test, and the police, which had given Reichelt permission to perform the test with a dummy, were there to maintain order. Reichelt’s arrival, however, also brought with it the surprise that he intended to perform the test himself.

Before he climbed the stairs up to the first platform, Reichelt’s friends tried to talk him out of the jump. He remained determined to do it, and at 8:22 am, Reichelt stood upon a chair, which itself was upon a table. He opened up his parachute suit and stepped out onto the guardrail. He threw a piece of paper over the railing to check the direction of the wind. Satisfied, Reichelt followed, jumping from the ledge.

More from us: The Houdini Death Mystery: Appendicitis or a Spiritualistic Plot?

Reichelt’s parachute folded around him, and he fell the 187-foot distance in a matter of seconds. Hitting the ground, the impact created a crater 5.9 inches deep. It was reported that his right arm and leg were crushed, his spine and skull were broken, and blood was everywhere. He died upon impact, although he was officially declared dead at Necker Hospital. It was found via an autopsy that Reichelt had died of a heart attack during the fall.