Braveheart (1995) is a historical epic directed by and starring Mel Gibson. Set in late 13th-century Scotland, it depicts William Wallace’s life and the First War of Scottish Independence. Braveheart won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and it presents an action-packed, thrilling storyline that captivates audiences.

However, Braveheart isn’t as accurate as you might think. Here are a few historical inaccuracies featured in the film.

The real Braveheart

Braveheart is a fantastic name for a film. It’s also a historically accurate reference to a Scottish leader – but not William Wallace. The title is said to have referenced Robert the Bruce. Also known as Robert I, he reigned as King of Scots between 1306-29. He fought during the First War of Scottish Independence and led the Scots after Wallace’s death in 1305.

Upon his deathbed, Robert the Bruce asked his friend, Sir James Douglas, to carry his heart with him. According to Jean le Bel, Douglas was to carry it to the Holy Land and present it at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem as a show of penance. Alternatively, John Barbour says Douglas was to carry his heart simply into battle against “God’s foes.”

The name was coined when Douglas threw Robert the Bruce’s heart into battle, shouting, “Lead on Braveheart, as thou dost!” The heart was reportedly recovered from the battlefield and interred at Melrose Abby.

Jus Primae Noctis

In the film, Edward I – or Longshanks – invokes Jus Primae Noctis, meaning the “right of the first night.” This law gives nobles the right to have intimate relations with subordinate women, particularly on their wedding nights. Edward jokes in the film that “the trouble with Scotland is that it is full of Scots.” He then states, “If we can’t get them out, we’ll breed them out.” To accomplish this, he enacts what he calls “an old custom.”

While the invoking of this produces great emotion in Braveheart and pushes the Scots closer to fighting the English, a debate surrounds the idea, with many suggesting that it’s more myth than fact. Medieval scholar Albrecht Classen stated, “Practically all writers who make any such claims [of its existence] have never been able or willing to cite any trustworthy source if they have any.”

Some scholars have suggested that the “right of the first night” is actually only referenced in writings from later periods and, instead of actual law, it might have been a way for nobles to take advantage of those beneath them.

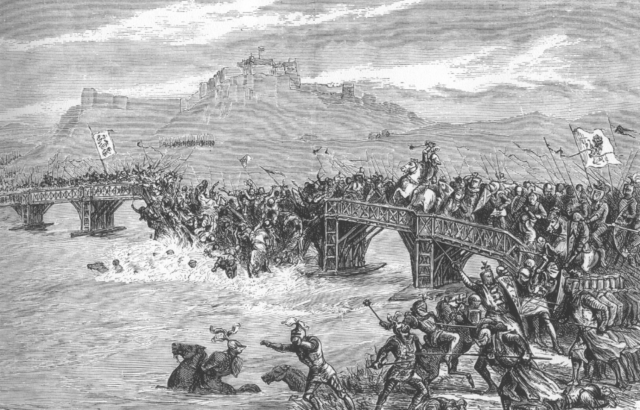

Battle of Stirling Bridge

The Battle of Stirling Bridge was fought on September 11, 1297. The battle is one of William Wallace’s most famous victories, and while it’s a terrific scene to watch as part of the film, it’s greatly inaccurate.

The first issue is the focus on Wallace. He was, of course, an integral part of the battle. However, the film completely leaves out Andrew Moray, also known as Andrew de Moray. In 1297, before Stirling Bridge, Moray raised a small army and began to fight against Edward I, retaking control of the north for John Baiol, King of Scots. He then merged forces with Wallace in advance of the Battle of Stirling Bridge.

Wallace is depicted as the mastermind behind the success of the engagement, when it was actually Moray, who became wounded during the fighting and died shortly after.

An even more grievous inaccuracy is that the Battle of Stirling Bridge presented on film bears little resemblance to the actual battle. If you’re thinking, “Wait, I don’t remember a bridge in the battle depicted in the film,” well, you’re right. The Battle of Stirling Bridge, unsurprisingly, actually took place on a bridge.

The Scots and English armies were located on either side of the River Forth, with the bridge being the safest way to cross. That being said, it was only wide enough for two horses to cross side by side. Wallace and Moray waited as the English began to cross. When a number they believed they could defeat had crossed, they attacked, leaving the English no place to retreat to, with only a few making it back over the bridge.

John de Warrenne, one of the English commanders, ordered the bridge be destroyed and retreated to Berwick, abandoning the lowlands to the Scots.

Isabella of France

Braveheart depicts Isabella of France as a mature woman who enters into a romantic entanglement with the Scottish rebel. It even goes so far as to suggest she becomes pregnant with William Wallace’s child.

That couldn’t be further from the truth – not to mention the two almost certainly never met.

Isabella did marry Edward II and was Queen Consort of England between 1308-27. One issue with her depiction in the film is her age. Isabella was born between April 1295 and January ’96, which made her only three years old and living in France at the time of the Battle of Falkirk. This is when the romantic element is depicted on-screen, which certainly didn’t take place in real life.

Tartan and war paint

The film shows William Wallace and the Scots wearing kilts with their clan tartans. It also shows them with blue paint on their faces during the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Both of these have become prominent in the public’s imagination surrounding Wallace and Scottish history. However, neither is accurate to the period.

Peter Traquair, a Scottish author, described these costume and makeup choices as a “farcical representation” of Wallace. He declared that Wallace wasn’t “painted with woad (1,000 years too late) running amok in a tartan kilt (500 years too early).”

Descriptions of Celtic warriors painting their bodies with dyes made from woad date back to Julius Caesar‘s own writings from the first century BC. Tartan kilts, on the other hand, weren’t introduced until the late 16th century, with the kilt as we know it today not created until the 18th century.

More from us: The Final Messages Sent From Titanic Provide an Eerie Minute-By-Minute Narrative

Despite these and several other inaccuracies, Braveheart is still an epic film that captivates audiences. Although the movie is certainly less authentic than it claims to be, that isn’t going to stop us from rewatching it!