The period following the War of 1812 ushered in what is commonly referred to as the Era of Good Feelings, marked by a significant reduction in partisan political strife and an increase in national unity. This time was characterized by the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party after the Federalist Party’s decline, leading to a political landscape with considerably less opposition. It was a moment in American history where the focus shifted towards internal improvements and fostering a sense of national pride.

The dawn of the Era of Good Feelings

Following the conclusion of the War of 1812, a significant shift began to emerge in the political and social landscape of the United States, marking the onset of what is historically referred to as the Era of Good Feelings. The term was credited back to Benjamin Russell, who first used it in the Boston Federalist newspaper Columbian Centinel on July 12, 1817. This period was characterized by a noticeable decline in partisan politics, as the Federalist Party began to dissolve and the Democratic-Republicans dominated, leading to a more unified national government. The war itself, often seen as the second war for American independence, fostered a strong sense of national pride and identity among the citizens. This newfound unity was a stark contrast to the intense political divisions that had characterized the early years of the republic.

The sense of national unity and the decline in political strife were not the only factors contributing to this unique period. Economic growth and territorial expansion also played critical roles. The American economy began to experience significant growth, partly due to protective tariffs that encouraged domestic manufacturing and partly due to the expansion of the country’s borders, which opened new lands for settlement. These developments contributed to a sense of optimism and possibility that permeated American society. People felt more connected to their country and optimistic about its future, laying the groundwork for what would be remembered as a relatively harmonious period in the nation’s history.

Economic prosperity and innovations during the Era of Good Feelings

During the Era of Good Feelings, the United States experienced an unprecedented economic boom, largely fueled by significant advancements in technology and infrastructure. The construction of the Erie Canal, for instance, was a monumental project that revolutionized transportation and commerce across the nation. By connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean, this engineering marvel facilitated the cheaper and faster movement of goods, catalyzing trade and encouraging westward expansion. Similarly, the onset of the Industrial Revolution within American borders marked a transformative period. Innovations in manufacturing processes and the introduction of mechanized production methods not only boosted productivity but also reshaped the country’s economic landscape, paving the way for the United States to become a burgeoning industrial power.

This period of optimism and progress was further characterized by the widespread adoption of new technologies that enhanced both the efficiency and reach of businesses. Steam power, for example, became a driving force behind industrial growth, powering factories and revolutionizing transportation on railroads and steamboats. The ripple effects of these technological advancements were profound, contributing to an atmosphere of economic prosperity and national confidence. Communities grew, and with them, the demand for goods and services, creating a self-sustaining cycle of growth and innovation. The collective impact of these developments during this time not only underscored the nation’s potential but also fostered a sense of unity and purpose among its people as they looked forward with optimism to the future possibilities that lay ahead.

The Era of Good Feelings and its impact on American politics

During the period known as the Era of Good Feelings, American politics underwent a significant transformation that fostered a sense of national unity and purpose. This unique time span, which roughly lasted from 1815 to 1825, was marked by a notable decline in partisan rivalry, primarily due to the collapse of the Federalist Party after the War of 1812. This left the Democratic-Republican Party as the sole dominating force in the political landscape. The absence of major political opposition facilitated a harmonious atmosphere, allowing for the implementation of policies that aimed at strengthening the federal government and promoting economic growth. This period also witnessed the presidency of James Monroe, who embarked on a goodwill tour, further symbolizing the newfound unity and contributing to the moniker of this tranquil epoch.

The impact of this harmonious period on American politics was profound. It saw the initiation of the American System, proposed by Henry Clay, which aimed at fostering economic self-sufficiency through protective tariffs, the establishment of a national bank, and investments in infrastructure projects. These policies not only stimulated economic growth but also laid the groundwork for a more interconnected and unified nation. However, this era was not devoid of challenges. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, for instance, exposed the underlying sectional tensions that would eventually erupt into the Civil War. Nonetheless, the Era of Good Feelings is remembered for its role in shaping a sense of American identity and nationalism, demonstrating how periods of political concord can significantly influence the trajectory of a nation’s development.

Cultural developments and national identity during this era

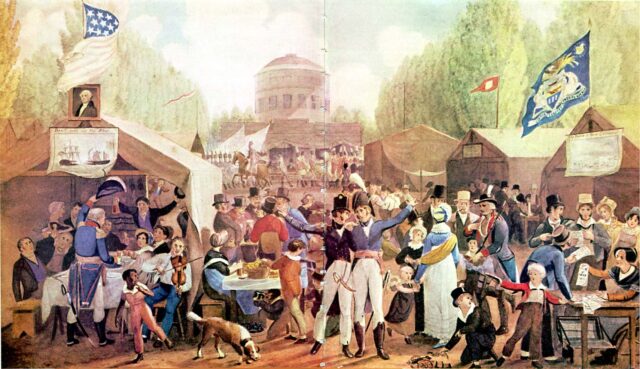

During the Era of Good Feelings, the United States experienced a profound transformation in its cultural landscape and national identity. Literature, arts, and educational reforms emerged as key areas through which this identity was expressed and reinforced. Notably, American writers began to gain prominence, moving away from European influences and focusing on themes that reflected the American experience. This was a time when figures such as Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper captured the imagination of the public with works that rooted themselves in the American landscape and ethos. Their stories and characters, rich with the flavor of American culture and settings, contributed significantly to the development of a national literary voice.

Simultaneously, the visual arts flourished, with artists like Thomas Cole leading the way in the Hudson River School of Painting, which celebrated the natural beauty of the American landscape. These artworks not only provided a visual representation of the country’s majestic wilderness but also symbolized the growing sense of national pride and unity. Furthermore, educational reforms aimed at expanding access to education for more Americans helped to foster a sense of informed patriotism. Schools began to incorporate studies that emphasized American history and government, shaping the minds of young Americans to appreciate their country’s unique heritage and democratic ideals. Through these cultural expressions, the era contributed profoundly to the consolidation of an American identity that was distinct and robust, reflecting the optimistic spirit of the time.

Read more: War of 1812: The Burning of Washington and how a Freak Storm Saved the Day

Reflecting on the Era of Good Feelings, it’s essential to delve into the nuances that characterized this period in American history. On the surface, it was a time marked by a sense of national unity and political calm following the War of 1812. This era saw the dissolution of the Federalist Party, leaving the Democratic-Republican Party as the sole political entity, which ostensibly led to a harmonious political landscape. The question arises: was this era genuinely one of cohesive national sentiment, or did it merely mask underlying divisions that would later come to the fore? This reflection invites a deeper examination of the era’s lasting impacts on American society and politics, challenging us to consider the multifaceted nature of historical periods that are often romanticized for their surface-level tranquility.