Nigerian writer and journalist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani spoke to the BBC recently as part of their “Letters from Africa” series. Nwaubani documented how she discovered that there is a throne reserved for the Queen of England in a West African state.

The Kingdom of Efik

The Efik people are found in the south-eastern corner of what is now Cross River state in Nigeria. At the beginning of the 18th century, they occupied the town of Calabar. The hierarchy included various chiefs and kings (although today there is only one king, known as the Obong of Calabar).

Initially, the economy was based on fishing, but the area developed into a major trading center during the 19th century. European ships would dock and trade their products for slaves and palm oil products. As time went on, the Efik people became middlemen between the slave traders from Liverpool and Bristol and inland African traders.

The Efik people were very taken with the European culture and assimilated it into their own culture. They dressed in European fashions and even followed Christianity thanks to the work of missionaries such as Mary Slessor.

Cultural influences were so strong that the Efik people even began adopting English surnames in place of their traditional African ones. As such, families named Donald, Henshaw, Duke, and Clark appeared across the kingdom.

Queen Victoria’s offer of protection and trade

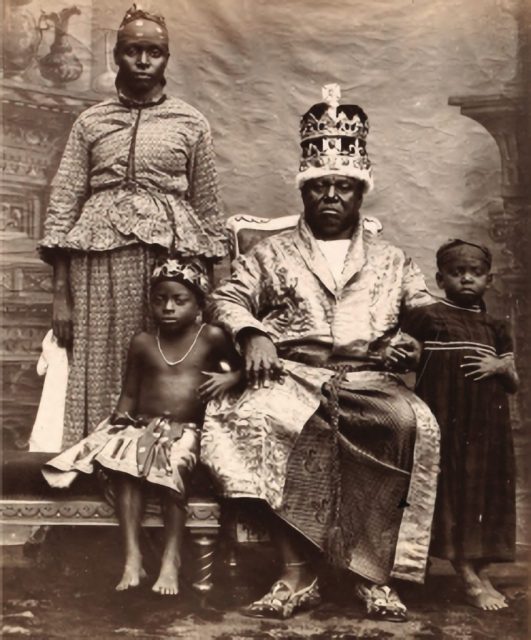

During the reign of Queen Victoria, there were two kings in the coastal town of Calabar: King Eyamba V of Duke Town and King Eyo Honesty II of Creek Town. At this time, Calabar had become an important source of palm oil for industrial Britain.

In addition, although the slave trade had been prohibited by British law in 1807, the practice was not outlawed in all British territories. It is believed that between 1720 and 1830, around one million slaves left Calabar on British ships.

Keen to maintain trade links with this African kingdom, Queen Victoria wrote to King Eyamba directly. She promised inducements and protection if they continued as trading partners, although she indicated that she was not interested in trading human cargo. Instead, she was hoping for spices, palm oil, and glassware, among other things.

The mistranslation

Queen Victoria signed her letters as “Queen Victoria, The Queen of England.” Unfortunately, an interpreter mistranslated this when reading the letter to King Eyamba and proclaimed her “The Queen of All White Men.” Such an honorific caught the attention of King Eyamba and set him to thinking.

King Eyamba informed his elders that if he was going to accept protection from a woman, it was only right that the woman was his wife. As such, he wrote back proposing marriage and signed his letter as “King Eyamba, the King of All Black Men.”

According to Charles Effiong Offiong-Obo, an Efik chief who is also the scribe of the Duke Town clan: “He wrote to the Queen and said he wanted to marry her so that the two of them would rule the world.” He adds that King Eyamba “was adventurous and dictatorial.”

Find yourself reminiscing about the past? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive nostalgic content directly to your inbox!

A proposal not quite rejected

One might think that diplomatic relations would have been quick to rectify this misunderstanding, but history shows that’s not the case. Instead, Queen Victoria acknowledged receipt of his letter, stating that she looked forward to future trade relations. She also sent him some gifts which included a royal cape, a sword, and a Bible.

While there was no explicit written acceptance, the king interpreted the sending of gifts as in implicit acceptance. Accordingly, he set up a seat beside his throne, ready for his new bride, the Queen of England.

After that, the two monarchs continued to correspond, and some of the letters are now on display at the National Museum in Calabar. At one point, an anonymous buyer purchased various missives, and there are those who believe that this was the British Royal family trying to destroy evidence of an affair between the king and queen.

A tradition continued today

Even today, the coronation of the Obong of Calabar still references this royal “marriage” and includes two thrones — one for the Obong and one for the Queen of England. In her absence, a Bible is placed on the queen’s chair. The Obong’s actual wife sits behind him.

When the second part of the coronation commences in a Presbyterian church, the Obong wears a crown and cape that is custom-made in England for the ceremony.

It was Donald Duke who uncovered the original letters and brought this interesting piece of history to light. He was governor of Calabar between 1999 and 2007, during which time he made extensive renovations to the National Museum.

He revealed to Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani: “I first heard about it around 2001, when I was passing by the museum and saw this very interesting correspondence between Queen Victoria and King Eyamba… I thought it was important that we document our history, so we did a lot of research.”