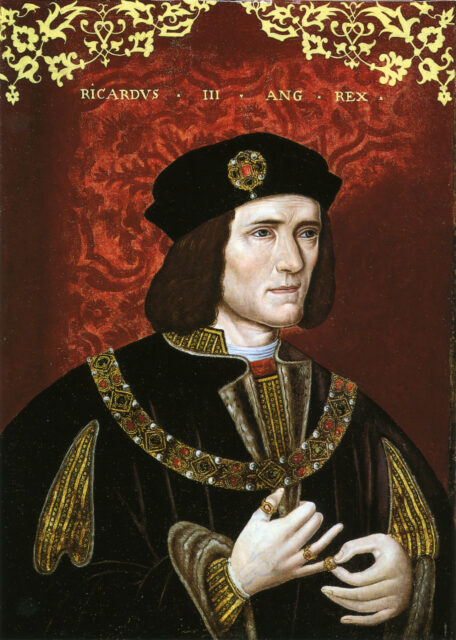

Richard III was the King of England from 1483-85, when he died during the Battle of Bosworth Field. His death marked the end of the House of York and the Plantagenet Dynasty. His defeat also saw the end of both the Wars of the Roses and the Middle Ages in England.

Partially thanks to William Shakespeare, Richard III has been remembered as one of history’s greatest villains. Following his death, he was buried in Greyfriars, Leicester. In 1538, however, the dissolution and demolition of the friary led to his tomb becoming lost.

While rumors circulated that his remains had been thrown into the River Soar, Richard III’s body remained in its original tomb, and did so for over 500 years. This is the story of his death and the over 500-year search for the “Car Park King.” Continue reading to learn more…

Battle of Bosworth Field

In August 1485, the Battle of Bosworth Field took place. The engagement was fought between the armies of the House of York, under the command of King Richard III, and the House of Tudor, under the command of Henry Tudor.

Bosworth Field was the final major battle of the Wars of the Roses, which had been fought across England for over 32 years. Upon its conclusion, Tudor’s army was victorious. Richard III was killed and Tudor ascended to the throne as Henry VII, the first king of the House of Tudor.

Rumors circulate over the location of King Richard III’s remains

After his death, Richard III was reportedly stripped naked and taken to Leicester for public display. On August 25, 1485, he was buried “at the convent of Franciscan monks in Leicester… [with] no funeral solemnity.” Ten years later, Henry VII paid for a monument to mark the burial site. With few descriptions existing, it’s hard to know what it looked like. However, it was reported to feature Richard III’s image.

The dissolution of Greyfriars in 1538 led to the demolition of the friary and, likely, the monument. To mark the former king’s grave, a small stone pillar with the inscription, “Here lies the Body of Richard III, Some Time King of England,” was erected.

By 1844, the marker was no longer there. Stories later circulated that Richard III’s body had been taken and thrown into a nearby river. However, historians have come to the conclusion that the author of the tales made up a reason as to why the former king’s body wasn’t found where it had originally been buried. In actuality, they were just in the wrong place.

The site of Richard III’s burial was eventually forgotten. It was soon built upon, and by the time of its discovery had become a car park for Leicester City Council.

Search for a lost king

The driving force behind the search for Richard III’s remains was the Richard III Society. They’d first suggested in 1975 that his remains may be under the car park. This was reiterated by historian David Baldwin in 1986, who speculated, “It is possible (though now perhaps unlikely) that at some time in the twenty-first century, an excavator may yet reveal the slight remains of this famous monarch.”

It wasn’t until 2004-05 that Philippa Langley of the society’s Scottish branch looked deeper into the theory. Convinced Richard III was, in fact, under the car park, she asked historian John Ashdown-Hill to contact Channel 4’s Time Team. The TV series saw a team of archaeologists excavate sites across England. However, they only filmed three-day digs, meaning the project was out of their scope.

Three years passed before Langely found what she described as her “smoking gun.” It was a medieval map of Leicester, showing Greyfriars Church. When compared to the modern layout, the site was located beneath the car park.

The “Looking for Richard: In Search of a King” project soon gained significant support, leading to an official excavation. The Richard III Society, Leicester City Council, and the University of Leicester provided support and funding.

Skeletal remains are discovered beneath the car park

In 2011, initial surveys of the car park took place. Using ground-penetrating radar, the team located modern elements that would be in their way, including pipes and cables. It was decided two trenches would be dug, with work starting on August 22, 2012 – 527 years since Richard III’s died.

Within six hours of digging the first trench, human remains were found. It would take five months of research and testing, but the skeleton was confirmed to be that of Richard III.

It was unearthed with battle wounds and a curved spine, both strong indicators that it was Richard III. Once exhumed, carbon dating showed the bones dated back to 1455-1540, when Richard had died. It was also discovered they belonged to a man in his late 20s or early 30s – Richard was 32.

The final step was comparing DNA with those of a confirmed relative. In 2005, Ashdown-Hill had discovered a mitochondrial DNA sequence shared between Richard III and his sister, Anne of York. It was confirmed with 99.999% accuracy that the body was, in fact, the late king.

Turi King conducted the DNA testing and said he “went really quiet. I was seeing all these matches coming back, thinking, ‘That’s a match, and that’s a match, and that’s a match.’ At that point, I did a little dance around the lab.”

The findings were publicly announced by the University of Leicester in February 2013. After more than 500 years, the lost king had, at last, been found.

Reinterment of King Richard III

The King Richard III Visitor Centre, dedicated to telling his story, opened in July 2014.

The formal reinterment of Richard III occurred at Leicester Cathedral in March 2015. The Archbishop of Canterbury led the service, which included actor Benedict Cumberbatch, a distant cousin, reading a poem by Carol Ann Duffy. Queen Elizabeth II was represented by the then-Countess of Wessex and sent a message describing the occasion as “an event of great national and international significance.”

More from us: The Real Life Mummy’s Curse? Ancient Remains Could Infect Humans

“This is not a funeral at which we mourn,” said Professor Gordon Campbell of the University of Leicester. The occasion was truly a fitting final farewell. His internment in 2015 gave Richard III what he’d so rightly deserved in 1485 and what he hadn’t been granted.